FCC’s New Drone Exemptions Open Loopholes for Retailers, But the Fine Print Matters

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

When the FCC dropped its sweeping foreign drone ban two weeks ago, practically everyone in the industry said the same thing: “A literal reading of this announcement can’t possibly be true, and it also can’t be legal.” FPV expert Joshua Bardwell was among those skeptics, and in a new video analysis, he breaks down how the FCC appears to have quietly walked back some of its most overreaching provisions while leaving critical questions unanswered.

The FCC fact sheet released January 7, 2026, creates two primary exemptions from the December 22 ban that added all foreign-made drones and components to the Covered List. But as Bardwell explains in his video, the real story isn’t just the exemptions themselves. It’s how they create potential pathways for U.S. retailers to continue importing drone components, even as DJI and Autel remain completely blocked.

The Blue UAS Exemption Won’t Help Most Hobbyists

The first exemption covers any UAS or UAS critical component on the Blue UAS cleared list. Bardwell is blunt about its practical impact:

“This is not going to do much for hobbyists because drones on the Blue UAS list are drones that are basically manufactured inside the United States and are sold mostly to the government, military, federal government, etc.”

Blue UAS platforms from manufacturers like Skydio, Parrot, and Teledyne FLIR weren’t designed for the hobbyist market. They command premium prices and lack the features recreational pilots expect. The exemption essentially codifies what was already true: domestically manufactured drones approved for government use aren’t the problem the FCC was trying to solve.

The 60% Domestic Content Loophole

The second exemption is where things get interesting. The FCC now applies the Buy American standard, which defines a “domestic end product” as anything manufactured in the United States where “the cost of its components exceeds 60% of the cost of all of its components.”

This means 40% of a drone’s components can still come from foreign sources. For FPV builders and U.S.-based drone manufacturers, this represents a significant softening from the original announcement’s apparent blanket ban on all foreign components.

But Bardwell highlights an even more significant provision buried in the Buy American definition:

“Components of foreign origin of the same class or kind as those that the agency determines are not mined, produced, or manufactured in sufficiently and reasonably available quantities or of sufficiently quality is treated as domestic.”

This is the real loophole. American manufacturers simply don’t produce many FPV components at scale. Flight controllers, ESCs, camera modules, and specialized motors overwhelmingly come from overseas suppliers. If retailers can demonstrate these components aren’t available domestically in sufficient quantity or quality, they may be able to continue importing them.

The “Dual-Use” Camera Question

The FCC fact sheet addresses a question that had alarmed many in the hobby: What about components that could go on a drone but have other uses?

According to the document, “UAS critical components means components designed and intended primarily for use in a UAS.” A camera with many potential functions that could theoretically attach to a drone is not classified as a UAS critical component. But a camera designed primarily as a drone camera would be.

Bardwell notes the inherent ambiguity: “A Runcam Night Eagle camera is intended to go on a drone in every real sense of the word. But then when it comes down to talking to the FCC, could you argue that, well, it could go on anything?”

The same logic could extend to flight controllers, which are fundamentally just specialized computers outputting signals to ESCs. Where exactly the line falls between “primarily for drones” and “general-purpose component that happens to work on drones” remains undefined.

The Motor and Battery Jurisdiction Question

The original December announcement listed motors and batteries as critical components, raising immediate questions about FCC jurisdiction. The FCC regulates radio frequency devices. Motors and passive batteries don’t transmit RF signals.

The new fact sheet’s answer is somewhat evasive: “No device now requires FCC equipment authorization that did not already require it.” In other words, the FCC isn’t claiming new regulatory authority over mechanical components.

However, the document adds that entities seeking waivers “will be required to establish an onshoring plan for the manufacturing of all UAS critical components, including components that do not require FCC authorization.”

This creates a strange situation where the FCC acknowledges it doesn’t regulate motors and batteries, but companies wanting exemptions must still demonstrate plans to onshore manufacturing of those components.

Who Actually Benefits From These Loopholes?

Bardwell’s assessment is pragmatic: individual hobbyists ordering from AliExpress or Banggood probably won’t face enforcement action.

“Hobbyists will be fine. It might be a little bit annoying not to be able to get things as quickly as if you bought them domestically.”

The real question is whether U.S. retailers can use these loopholes to continue importing and selling drone components. GetFPV, RaceDayQuads, and other specialty shops that supply the American FPV community source their inventory from overseas manufacturers. If those importation channels get blocked, hobbyists won’t be buying direct from China. They’ll be buying from diminishing domestic inventory or paying premium prices for the few domestically manufactured alternatives.

Bardwell’s read: “It seems to me that this is one of the biggest and most meaningful loopholes in the new definition that could be used to keep the FPV hobby in the United States going as much as it was threatened by this decision.”

DJI and Autel: Still Completely Blocked

None of these exemptions help DJI or Autel. Both companies remain on the Covered List, and the component ban means any drone containing their technology falls under restrictions regardless of branding.

This confirms what we’ve reported: DJI’s shell company strategy is dead. Even if a drone carries a different brand name, if it contains DJI components, it’s blocked. The onshoring requirement for waivers makes clear that simply rebranding isn’t a viable path forward.

DroneXL’s Take

Bardwell makes an observation that captures the fundamental dysfunction of this regulatory process:

“It’s a terrible way to do business. It’s a terrible way to run regulations. If anybody had asked before this went out what the effect would be, they would have heard all these problems, and this memo, these exemptions could have been built in from day one.”

He’s right. The FCC made sweeping proclamations, watched the industry panic, then quietly released clarifications that partially walk back the most extreme interpretations. This pattern, as Bardwell notes, is becoming standard practice:

“They seem to make wide ranging proclamations, and then when people freak out, sometimes, not always, they rewind and back up. Not quite to where they should have gone in the first place.”

The practical reality for most pilots: your existing gear is fine, retailers may find ways to keep importing hobby components through the newly defined loopholes, and DJI remains locked out of new product authorizations. But the uncertainty this regulatory chaos creates hurts American businesses that can’t plan inventory, manufacturers who can’t predict which components they can source, and pilots who don’t know what they’ll be able to buy six months from now.

The FCC’s January exemptions don’t fix the underlying problem. They just prove that even the agency issuing the ban didn’t fully think through what “all foreign-made drones and components” would actually mean in practice.

What do you think about the FCC’s exemptions? Do these loopholes provide enough flexibility for the U.S. drone industry, or is this just regulatory theater? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Editorial Note: AI tools were used to assist with research and archive retrieval for this article. All reporting, analysis, and editorial perspectives are by Haye Kesteloo.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

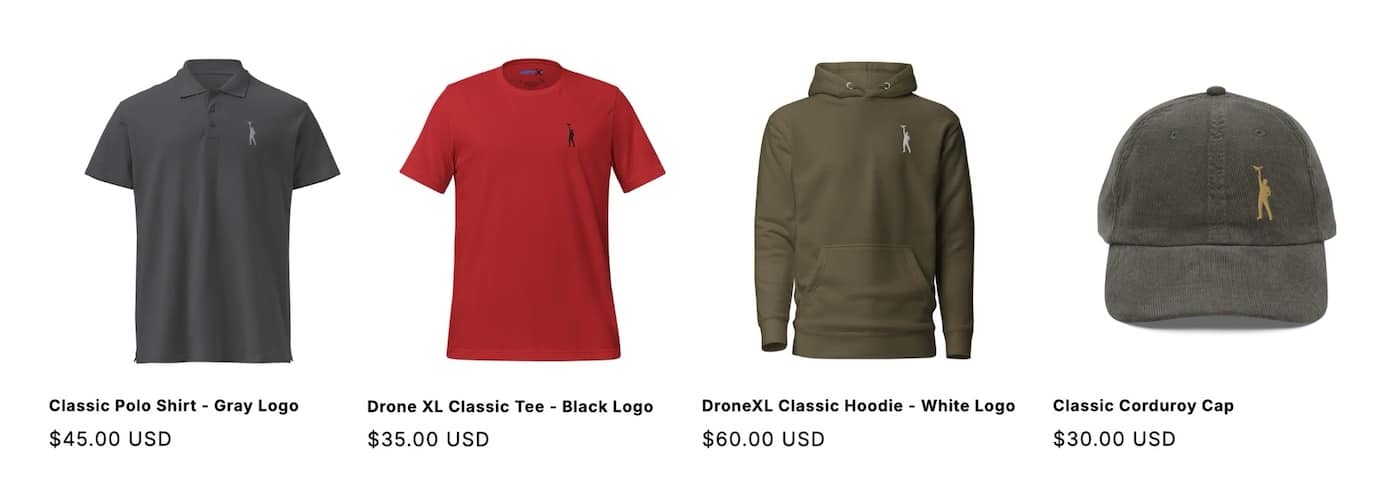

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.