Contraband is entering Georgia prisons from Drones again

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

Contraband delivery by drone has surged recently inside Georgia’s prison system, as reported by The Georgia Recorder. Previously, a months-long investigation that led to 150 arrests had driven drone activity down. In December, only 15 drone incidents had been reported. But by November, incidents climbed to 63, a sharp resurgence. The illicit drops range from drugs to cell phones. For many inmates, climbing ageing pipe chases to reach roofs or ceiling spaces has become a way to receive packages from outside.

Prison officials describe contraband as more than an occasional nuisance. Commissioner Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) head Tyrone Oliver says that flying contraband into prisons “can be a lucrative business.” Many of these facilities are decades old, with internal pipe chases and dorms that make them vulnerable. A drone flying low over a prison yard or roof might seem harmless to a casual observer but for inmates, it is an open invitation.

When staff spot a drone, the current protocol is limited: contact local law enforcement, deploy canine units, and search for suspicious vehicles or people near the prison. Discomfortingly, that is where the response ends. Federal law restricts prisons and local authorities from “touching” or disabling the drone even if it is hovering just above the facility. That means no shooting down drones, no jamming, no taking control. It is the same legal treatment a drone would receive if flying near a major airport.

This legal paralysis frustrates state lawmakers. Representative Danny Mathis asked how prison authorities could lack the authority to intercept a drone entering a clearly restricted area like a prison. Oliver agreed the laws need to change. He is lobbying at the federal level with agencies like the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and hopes that pressure from lawmakers can produce reform.

Until then, prisons remain vulnerable, reliant on after-the-fact searches and arrests instead of active drone defense.

The 2026 World Cup exposes how inconsistent drone defenses remain

At the same time, the United States is mobilizing major efforts to secure airspace ahead of the 2026 World Cup. In November 2025, the federal government announced a $500 million grant program dedicated to countering unauthorized drones. The grants are aimed at helping cities and law enforcement agencies deploy detection and mitigation tools. The plan includes funding for radar, signal detection, and, importantly, systems that can take control of or disable threatening drones.

The logic is straightforward: big events like the World Cup, along with upcoming national celebrations such as the 250th anniversary of the United States, draw crowds and present high-value targets. Drones are regarded by the White House Task Force and the National Security Council as among the top threats.

Photo credit: Federal Bureau of Investigations

To make this happen, the government is formulating pathways for state and local officers, previously constrained by law, to gain counter-drone powers. That includes training via a newly established national center, and a temporary deputization scheme so that officers can act under federal authority. Once certified, they can use mitigation tools such as jamming, remote takeovers, or other disruptive measures, always under coordination with federal agencies and the FAA.

In short, the same nation preparing to defend stadiums from rogue drones also admits that existing legal and technical barriers prevent public-safety actors from confronting those drones.

Why counter-UAS systems are critical beyond big events

This contrast highlights a critical point: drone threats and contraband don’t just come during mega-events. They come during everyday operations, including inside prisons, at critical infrastructure sites, border zones, hospitals, and more.

A counter-UAS (C-UAS) system is defined as any setup capable of detecting, tracking, identifying, and if needed neutralizing or mitigating an unmanned aircraft. Detection can rely on radar, radio-frequency sensors, acoustic, optical systems, or a fusion of those. Mitigation can include jamming control signals, taking over command of a hostile drone, or even physical interception.

In academic literature the need is clear: as drones proliferate and become more sophisticated, the risks to public safety, privacy, and security grow. Without active mitigation, detection alone is not enough. A detected drone is still a threat until it is neutralized.

In C-UAS doctrine, best practice is a layered, multi-tool defense: radar and RF detectors, signal intelligence, visual confirmation, electronic-warfare countermeasures, and, if necessary, kinetic or non-kinetic interdiction. Relying only on law enforcement patrols or visual spotting leaves too many vulnerabilities.

These systems have broad use cases: protecting stadiums, airports, prisons, nuclear facilities, prisons, and even remote infrastructure. The same toolkit being deployed for the 2026 World Cup could, in principle, protect prisons from contraband drones, if laws and budgets allowed it.

Prisons remain unprotected and exposed

Yet, places like the Georgia prison system remain in limbo. Despite bringing contraband and rising attacks, authorities do not have the legal authorization, nor in many cases the hardware to intercept drones delivering illegal cargo. The contrast with proactive World Cup security efforts is stark.

If a city hosting a stadium is considered high-risk and gets grants and new C-UAS systems, it begs the question: why not do the same for prisons? Prisons are high-security, closed perimeter facilities. They are natural targets for drone smugglers. A drone can bypass fences, walls, cameras anywhere an inmate could not reach otherwise.

Until legislatures act, prisons will continue relying on after-the-fact investigations: sniffing out suspects, arresting couriers, or hoping inmates don’t climb pipes. That is neither deterrence nor defense.

What must change to close the gap

- Legal reform: State and local law enforcement must be granted clear, lawful authority to deploy C-UAS systems in restricted airspace including correctional facilities. This includes the power to disrupt, seize, or destroy unauthorized drones.

- Budget allocations: Just as the federal government is funding drone security for the World Cup, similar grant programs should target prisons, especially in underfunded rural counties.

- Technology deployment: Prisons should receive layered C-UAS equipment radar/RF sensors, signal-jamming gear, and, where appropriate, interceptors. Detection is not enough; mitigation must be possible.

- Training and coordination: Staff must know how to operate the systems legally and effectively. Ideally, training could follow the model being used for the World Cup with oversight by federal agencies but usable at state/local level.

DroneXL’s Take

The rise in drone-delivered contraband inside prisons shows that drone threats are not limited to big events or warfare. They hit everyday people behind bars, institutional security, and public safety. The same counter-drone technology that the U.S. is deploying for the 2026 World Cup radar detection, signal jamming, drone interception could neutralize these threats. But until legal reforms and funding catch up, prisons will remain vulnerable. In a world where drones keep evolving, defense should not be optional it must be systematic and universal.

Photo credit: Ross Williams, Department of Justice and Wikimedia.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

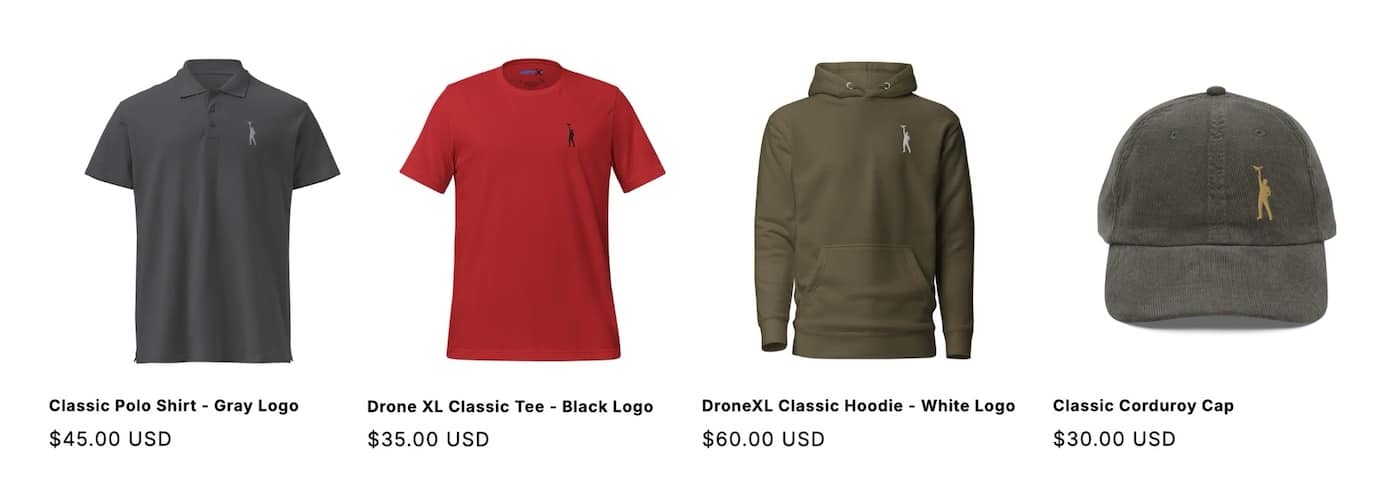

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.