Chip War Author: FCC Ban Succeeds Where Trump Tariffs Failed Against DJI

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

It was clear that Trump’s tariffs were never going to stop DJI. Now one of the most influential voices in US-China tech competition is making the same argument in the Financial Times.

Chris Miller, author of the Pulitzer Prize-finalist book “Chip War” that shaped Washington’s semiconductor policy, published an opinion piece this weekend analyzing why the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ban on foreign drones represents a more effective trade enforcement tool than the tariffs that came before it.

His analysis validates what we have been reporting at DroneXL for over a year: DJI simply moved production to Malaysia when Trump’s first administration imposed a 25% tariff on Chinese drones. The tariff did nothing.

- What: “Chip War” author analyzes FCC’s DJI ban as part of broader US-China tech competition

- Who: Chris Miller, semiconductor policy expert whose book influenced Washington’s chip strategy

- Key finding: In 2024, Malaysia exported three times as many drones by value to the US as China did

- The argument: FCC import bans are harder to circumvent than tariffs, which just relocate production

Miller’s piece appears less than two weeks after the December 22 ban that added all foreign-made drones and critical components to the agency’s Covered List.

The Malaysia Pivot We Have Been Documenting

Miller’s most striking data point: “In 2024, Malaysia exported three times as many drones by value to the US as China did.”

That number quantifies something we have been tracking since security researcher Konrad Iturbe first exposed DJI’s shell company network in 2024. Companies like Skyany, Skyrover, Cogito, Jovistar, and Fikaxo are selling DJI-designed drones manufactured in Malaysia under alternative brand names. The Malaysia pivot was DJI’s answer to Trump’s first-term tariffs.

“The ease with which China’s drone industry shifted production shows why globalized supply chains make tariffs a blunt and often ineffective tool,” Miller writes.

He is right. DJI did not absorb the 25% duty. They did not pass it to consumers. They simply moved final assembly across a border and kept selling at mostly the same prices. The tariff became irrelevant.

Why the FCC Approach Is Different

Miller frames the FCC’s Covered List mechanism as a fundamentally different enforcement tool than tariffs. The FCC does not tax imports. It blocks them entirely by denying the radio frequency authorizations that drones need to legally operate in the United States.

“The FCC has authority to ban imports of any communications equipment that it believes facilitates espionage or threatens critical infrastructure,” Miller explains. “From internet routers to drones, as the range of communication equipment increases so does the FCC’s authority.”

For drone pilots, this distinction matters enormously. A tariff makes DJI drones more expensive. An FCC ban makes new DJI drones unavailable at any price.

As we know, the December 22 action went beyond DJI. The FCC added all foreign-made drones and critical components including flight controllers, batteries, motors, navigation systems, and ground control stations to its Covered List. As we reported, your existing drones still work and previously authorized models remain legal. But new products from any foreign manufacturer now face the same barrier.

The Scale Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss

Miller identifies the fundamental challenge that no policy tool can solve: China’s manufacturing scale advantage makes American alternatives uncompetitive regardless of which regulatory approach Washington chooses.

“China’s DJI is estimated to sell more than half the world’s cheap, first-person view drones,” Miller writes. “Because of this, China is also the leader in producing many key drone components. This provides major advantages. Companies can only justify developing specialized chips and other hardware if they can amortize the cost over many units sold. China’s market dominance has made it impossible for foreign companies to compete.”

This is the uncomfortable truth that gets lost in security debates. Even if DJI genuinely posed a national security risk, banning them does not automatically create viable American alternatives. The economics of drone manufacturing favor scale, and China has decades of head start.

We saw this play out in real time when China cut off Skydio’s battery supply in October 2024. America’s largest drone manufacturer was forced to ration batteries to one per drone. The company that lobbied hardest for DJI restrictions was itself dependent on Chinese components.

The Pentagon’s 300,000 Drone Goal

Miller notes that the Trump administration has outlined a “drone dominance” strategy with the Pentagon planning to purchase 300,000 small attack drones by 2028. The Russia-Ukraine war exposed a “drone gap” in American defense production, and Washington is scrambling to close it.

This aligns with what we have been tracking. The Army announced plans to purchase at least 1 million drones over the next two to three years. The Pentagon’s DOGE unit seized control of military drone procurement after the Replicator program’s failures, targeting acquisition of at least 30,000 drones in the coming months.

Miller highlights how US companies still rely on China for key components like batteries and motors:

“In 2024, China cut off battery sales to US drone companies, forcing makers like Skydio to ration battery sales.”

We reported last week on this exact contradiction. The FCC banned foreign batteries, but China makes 99% of them. The ban does not solve the supply chain problem. It just adds paperwork to it.

DroneXL’s Take

Chris Miller is not a drone industry insider. He is a semiconductor historian whose book literally shaped how Washington thinks about US-China technology competition. When someone at his level starts writing about drones in the Financial Times, it signals that our industry has officially become part of the broader tech decoupling conversation.

Here is what I expect: Miller’s framing of the FCC as a more effective enforcement mechanism than tariffs will influence how policymakers approach future restrictions. His validation of the Malaysia loophole problem will put pressure on the administration to expand enforcement to allied countries that serve as transshipment points for Chinese technology.

For Part 107 operators and recreational drone pilots, the takeaway is clear. The regulatory environment is not getting easier. Washington has found a tool that works better than tariffs, and they are going to keep using it. The December 22 FCC action was not an endpoint. It was a proof of concept.

Miller concludes that “targeted import restrictions could look more attractive than blanket tariffs” going forward. I agree. The question for drone pilots is not whether more restrictions are coming. It is how quickly American manufacturers can scale up to fill the gap, and at what price point.

Based on everything we have covered, including Skydio’s retreat from consumer markets, ongoing Chinese component dependence, and the Pentagon’s own procurement struggles, that gap is not closing anytime soon.

What do you think about Miller’s analysis? Does the FCC ban approach make more sense than tariffs for addressing national security concerns? Let us know in the comments.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

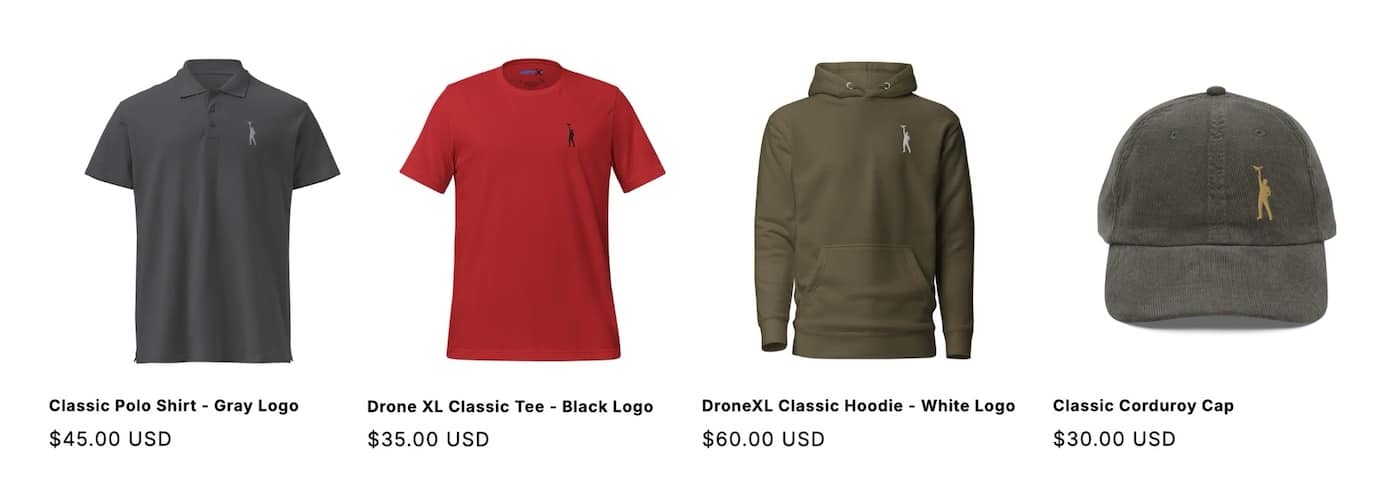

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.