Las Vegas Police Now Run America’s Largest Drone Program, But Won’t Say What It Costs

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

I’ve been tracking drone-as-first-responder programs across the country for years, and the numbers Las Vegas Metropolitan Police unveiled this week stop me cold. Ten thousand drone flights in 2025. More than any other law enforcement agency in the United States. And when they expect to double that volume in 2026, we’re watching the template for American police drone operations take shape in the Nevada desert.

But here’s what caught my attention at Wednesday’s press conference: Sheriff Kevin McMahill talked about technology, partnerships, and innovation. What he didn’t talk about was how much this costs taxpayers, or how the department plans to handle the civil liberties questions that inevitably follow this kind of surveillance expansion.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal reported on the unveiling of LVMPD’s expanded Fusion Watch and Drone Operations Center, which now includes 13 skyport rooftop launch pads across the valley, 75 drones in the fleet, and eight pilot bays running around the clock. This builds on the rooftop network we first reported in September 2025, when the department announced its ambitious expansion plans.

The Scale Changes Everything

Let me put 10,000 annual flights in perspective. Approximately 1,500 US law enforcement agencies now operate drone programs, representing a 150% increase since 2018. Most of those programs log a few hundred flights per year. Some of the more aggressive departments hit a thousand. Las Vegas just reported ten times that volume, and Assistant Sheriff Dori Koren said they’re anticipating roughly 1,700 flights per month in 2026, which would put them above 20,000 annual missions.

The operational model is straightforward. Of the 75 drones in Metro’s fleet, 38 are “dock” drones housed at the 13 skyports and remotely operated by pilots in the Fusion Watch center. Pilots include both Metro employees and trained civilians. Drones can reach a call within two minutes if it falls within roughly a two-mile radius of a launch site. Patrol officers can now request a drone ahead of their arrival, giving them real-time intelligence about what they’ll encounter.

“This is a paradigm shift in police work,” said Steven Oscar, program manager for the drone operation center. “We’re able to get an aerial asset up so that we don’t have any surprises for our police officers.”

The department cited a recent case where thermal imaging located a missing 9-year-old child in someone else’s backyard. That’s exactly the kind of use case that makes DFR programs compelling, and it’s why I’ve generally supported this technology for genuine emergency response.

Silicon Valley Money Meets Police Surveillance

The hardware comes from Skydio, the San Mateo-based company that has positioned itself as the American alternative to DJI. CEO Adam Bry attended Wednesday’s press conference, and the partnership highlights how Skydio has aggressively pursued government contracts while DJI faces mounting regulatory pressure.

What makes Las Vegas different from other DFR programs is the funding model. Metro officials explicitly declined to discuss costs at Wednesday’s event, but Sheriff McMahill did acknowledge the private partners: Skydio, Helix Electric, Martin-Harris Construction, and most notably, the Horowitz Family Foundation.

Ben Horowitz is a Silicon Valley venture capitalist whose firm Andreessen Horowitz has invested in Skydio and numerous other tech companies. His foundation is now funding police drone infrastructure in Las Vegas.

“This is what a public-private partnership looks like when it’s done right,” McMahill said. “Their commitment is rooted in a genuine belief in public safety, innovation, and a responsibility to invest in solutions that save lives.”

I’ve covered enough DFR programs to know what these systems cost. When we analyzed Cincinnati’s Skydio DFR deployment, the all-in cost worked out to roughly $62,343 per drone plus $450,000 annually for software and maintenance. Scale that to 75 aircraft and 13 skyport installations, and Las Vegas is almost certainly looking at a multi-million dollar annual operation. The public deserves to know whether their tax dollars are covering that, or whether a Silicon Valley foundation is subsidizing police surveillance infrastructure.

The ICE Question Nobody Wants to Answer

Athar Haseebullah, executive director of the ACLU of Nevada, raised the concern that’s been gnawing at civil liberties advocates since Las Vegas first announced its expansion plans.

“We don’t know the full extent of how our law enforcement agencies in Nevada are cooperating with the federal government and with ICE,” Haseebullah told the Review-Journal. “Are we just to trust the police and trust government when they’re engaging in massive surveillance efforts? How do we know that data won’t be turned over to the federal government or private surveillance companies?”

Koren’s response was the standard assurance:

“Every flight is tied to a legitimate public safety purpose. Every flight is logged and de-conflicted and audited and the data used is limited, reviewed and policy-driven.”

But we’ve seen how these assurances play out in practice. The NYPD flew 4.7-pound Skydio drones directly over protest crowds in violation of their own safety policies. Rochester Police explicitly budgeted state funds for surveillance drones to monitor protests. What starts as emergency response technology has a pattern of morphing into something broader.

Multi-Agency Access Expands the Footprint

One detail from the press conference deserves more attention. Oscar said the drone initiative is county-wide, meaning other agencies like Henderson Police Department and North Las Vegas Police Department can request drone support. The Fusion Watch center isn’t just serving Metro; it’s becoming regional surveillance infrastructure.

“It could be a house on fire or maybe Henderson needs help,” Oscar said. “We’re coming to help wherever we can with the drones.”

From an efficiency standpoint, that makes sense. From a civil liberties standpoint, it means multiple agencies can now access a surveillance network without having to justify their own drone programs to their own city councils or oversight bodies.

DroneXL’s Take

Las Vegas has built something genuinely unprecedented: a 24/7 drone surveillance network that responds to calls faster than officers can drive there, funded at least partly by private money that shields the program from normal budget scrutiny. Sheriff McMahill’s campaign promise to make LVMPD “the most technologically advanced police department in this country” is becoming reality.

The legitimate use cases are real. Finding missing children. Giving officers better situational awareness before they walk into dangerous scenes. Resolving some calls without sending patrol units at all. I’ve seen the data from Chula Vista’s pioneering program, and DFR technology demonstrably saves lives and stretches limited police resources.

But 10,000 flights per year, soon to be 20,000, operated by a mix of police officers and civilians, with data policies that nobody outside the department can verify, funded by a combination of public money and private foundation dollars that Metro won’t quantify, that’s not just a drone program. That’s the infrastructure for persistent aerial surveillance of an entire metropolitan area.

Other cities are watching Las Vegas closely. Skydio is positioning this partnership as a model for departments nationwide. The question isn’t whether this technology works; it clearly does. The question is whether the public accountability mechanisms can keep pace with the operational expansion.

My prediction: we’ll see at least three more major metros announce similar public-private DFR partnerships by the end of 2026, following Las Vegas’s template. And we’ll see at least one major legal challenge testing whether this level of aerial surveillance requires warrant protections, building on the Sonoma County ACLU lawsuit that’s already working through California courts.

What’s your take? Are programs like this the future of policing, or are we normalizing surveillance infrastructure that will be difficult to constrain once it’s built?

Editorial Note: AI tools were used to assist with research and archive retrieval for this article. All reporting, analysis, and editorial perspectives are by Haye Kesteloo.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

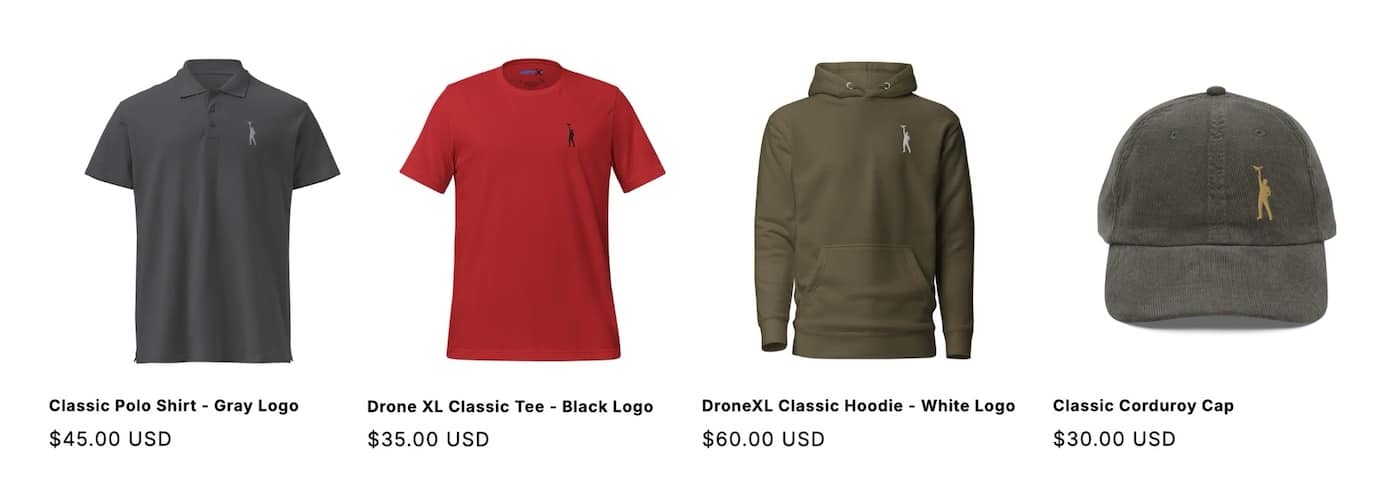

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.