Pentagon DIU wants containerized drone launchers that store, launch, and recover swarms on command

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

The Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) just published a solicitation for something the U.S. military has needed for years but never had: a box that can store drones, launch them in mass, recover them, recharge them, and do it all over again with almost no humans involved. The program is called the Containerized Autonomous Drone Delivery System, or CADDS, and the requirements read like a wish list pulled directly from lessons learned in Ukraine.

Here is what you need to know:

- The development: DIU issued a Commercial Solutions Opening seeking containerized systems that can store, rapidly deploy, recover, and refit multiple drones with minimal human involvement, operating from both land and sea platforms.

- The problem it solves: The U.S. military currently relies on a one-to-one operator-to-drone model that limits how fast and how many drones can get into the air. CADDS aims to break that ratio entirely.

- What makes this different: Unlike existing containerized launchers from Rheinmetall, UVision, and others that focus only on launching, CADDS requires recovery and refit capabilities built into the same container.

- The source: The War Zone first reported on the CADDS solicitation, with Joseph Trevithick providing a thorough breakdown of the requirements and the existing market for such systems.

DIU’s CADDS solicitation targets the Pentagon’s biggest drone bottleneck

The Containerized Autonomous Drone Delivery System is a Pentagon program run through DIU’s Commercial Solutions Opening process, seeking industry proposals for transportable, containerized platforms that autonomously store, launch, recover, and refit unmanned aerial systems for both persistent coverage and massed effects with a crew of no more than two personnel.

The solicitation language is blunt about the problem. “The Department of War faces a robotic mass challenge: current methods for deploying and sustaining unmanned aerial systems rely on direct human interaction to launch, recover, and refit each system,” the CADDS notice states. “This 1:1 operator-to-aircraft model limits deployment speed and scale while exposing operators to unnecessary risks.”

That 1:1 bottleneck has been the single largest constraint on how the U.S. military fields drones. The Army has announced plans to purchase at least one million drones over the next two to three years. The Drone Dominance Program is spending a billion dollars to acquire hundreds of thousands of kamikaze drones through 2028. But buying drones is only half the problem. Getting them airborne, recovered, refitted, and launched again at scale requires infrastructure that does not exist yet in the U.S. arsenal.

CADDS is DIU’s answer to that gap.

The technical requirements go beyond anything currently fielded

The CADDS requirements describe a system capable of storing drones in a dormant state for extended periods, then launching them on command. It must provide automated functions for storage, launching, recovering, and refitting drones within the containerized platform. Setup and breakdown must be measured in minutes, not hours. The system must work on land, at sea, in daylight and darkness, and in bad weather.

DIU does not name specific drone models the CADDS must accommodate. Instead, the solicitation says the system will need to support “homogeneous and heterogeneous mixes of Government-directed UAS.” That is a significant ask. It means the container cannot be built around a single airframe. It has to handle different types of drones simultaneously, which points toward a software-defined architecture where the container adapts to whatever gets loaded into it.

The autonomy requirements are also telling. DIU says CADDS must support “both operator-on-the-loop and operator-in-the-loop decision-making processes.” That distinction matters. Operator-in-the-loop means a human approves each action. Operator-on-the-loop means the system acts independently while a human monitors and can intervene. CADDS is being designed for the latter, which aligns with the AI-powered drone swarm concepts that Ukraine has already deployed in combat.

Existing containerized launchers fall short of what CADDS demands

The market for containerized drone launchers has been growing for years. We covered Rheinmetall’s containerized launcher for Hero kamikaze drones in 2024, a system built into modified shipping containers with 126 launch cells arranged in three 42-cell arrays, developed in partnership with Israeli company UVision. Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries showed a truck-mounted container holding 48 attack drones last year. Northrop Grumman’s Modular Payload System has been adapted to launch drones after originally being designed for anti-radiation missiles.

But almost all of these systems share the same limitation: they launch drones and that is it. Recovery and refit are handled separately, if at all. CADDS demands all three functions in one container.

The closest existing parallel is, oddly enough, not military. The War Zone points to Chinese company DAMODA, which rolled out an Automated Drone Swarm Container System last year for drone light shows. The system launches, recovers, and recharges thousands of small electric quadcopters at the push of a button. It is designed for entertainment, not combat. But the functional concept, a self-contained box that autonomously cycles drones through launch-recover-recharge loops, maps almost perfectly onto what DIU is asking for with CADDS.

Commercial drone-in-a-box systems from DJI and companies like Heisha also offer automated docking and recharging, but they typically handle one drone at a time. CADDS needs to manage dozens or more simultaneously.

Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb proved the containerized launch concept works in combat

The real-world validation for containerized drone launchers came on June 1, 2025, when Ukraine executed Operation Spiderweb, launching 117 FPV drones from modified trucks positioned near Russian airbases. The drones were hidden inside wooden crates on commercial tractor-trailers. Some trucks had retractable roof panels that opened remotely for launch. Others included self-destruct mechanisms.

The operation struck five airbases, including targets over 2,500 miles from Ukraine’s border, and destroyed over 40 Russian strategic bombers. The estimated damage exceeded $7 billion. The entire effort was 18 months in planning.

Operation Spiderweb was improvised. The Ukrainians built covert launchers from civilian vehicles because they had no alternative. CADDS aims to give the U.S. military a purpose-built version of the same concept, with the added ability to recover and reuse drones rather than treating each launch as a one-way trip.

CADDS fits into the Pentagon’s broader push to field drones at unprecedented scale

This solicitation does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of a military-wide pivot toward mass drone deployment that has accelerated dramatically over the past year.

Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll told Reuters the service plans to buy at least one million drones over the next two to three years. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s July 2025 memorandum reclassified small drones as “consumable” supplies, allowing field commanders to procure them directly. The DOGE unit took control of military drone procurement after the Replicator program’s repeated failures. Trump’s June 2025 executive order directed federal agencies to prioritize American-manufactured drones.

But buying drones at scale means nothing if you cannot deploy them at scale. A soldier still has to unbox each drone, calibrate it, pair a controller, launch it manually, and operate it one-to-one. That process cannot keep up with the volumes the Pentagon is now purchasing. CADDS is the infrastructure layer that bridges the gap between procurement and deployment.

The Replicator program’s failures showed exactly what happens when you try to network drones from multiple manufacturers without standardized infrastructure. Systems from different vendors could not communicate. Target recognition software failed during drills. A BlackSea Technologies unmanned boat went adrift from steering failure. CADDS, by requiring support for heterogeneous drone mixes within a standardized container, is an attempt to solve the interoperability problem at the infrastructure level rather than the software level.

The competition is already ahead

China has been particularly active in developing containerized drone systems. We reported on China’s PLA demonstrating a 200-drone swarm controlled by a single soldier in January. Chinese firms have displayed multiple truck-mounted swarm launchers at defense expos. DAMODA’s entertainment system already does what CADDS wants to do, minus the weapons.

Iran has used container-launched Shahed kamikaze drones for years. Taiwan, Turkey, and Israel are all pursuing similar capabilities. Auterion, the Swiss-American company, demonstrated a hybrid drone swarm completing the first multi-manufacturer kill chain in Munich in December 2025, showing that drones from three separate companies can operate under one software architecture.

The U.S. is late to this game. The New York Times warned in December that the Pentagon consistently loses war games against China, in part because America’s military remains built around expensive, vulnerable platforms while adversaries field cheap alternatives at scale.

DroneXL’s Take

I’ve been covering the Pentagon’s drone procurement struggles since the Replicator program first started falling apart in 2025. The pattern has been consistent: ambitious goals, bureaucratic delays, technical failures, and organizational reshuffles. CADDS breaks from that pattern in one important way. It is not trying to build the drones themselves. It is building the box that makes the drones useful at scale.

That distinction matters more than it sounds. The U.S. has no shortage of companies that can build small drones. Neros, Red Cat, Skydio, and dozens of others are ramping production. The missing piece has always been deployment infrastructure. How do you get 500 drones airborne in five minutes from a single location with two people? That is what CADDS is solving.

Ukraine proved the concept works with Operation Spiderweb, using improvised launchers hidden in civilian trucks. DAMODA proved the recovery-and-recharge loop works with their entertainment system. CADDS is the Pentagon’s attempt to combine both ideas into a hardened, military-grade platform. The real question is execution speed. DIU’s Commercial Solutions Opening process can move faster than traditional defense procurement, but “faster” in Pentagon terms still often means years.

I expect we will see initial CADDS prototypes by late 2026, with the first systems fielded to operational units by mid-2027 at the earliest. Companies already building drone-in-a-box systems for commercial applications, particularly those with open-architecture software, are best positioned to win this contract. Watch for Auterion’s partners and the defense primes that have already invested in containerized launch concepts, like Rheinmetall and Northrop Grumman, to submit proposals.

The irony here is hard to miss. The closest existing system to what CADDS describes was built by a Chinese entertainment company for drone light shows. The Pentagon is now asking American industry to replicate that capability for warfare. If that does not capture the current state of the drone gap, nothing does.

Editorial Note: AI tools were used to assist with research and archive retrieval for this article. All reporting, analysis, and editorial perspectives are by Haye Kesteloo.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

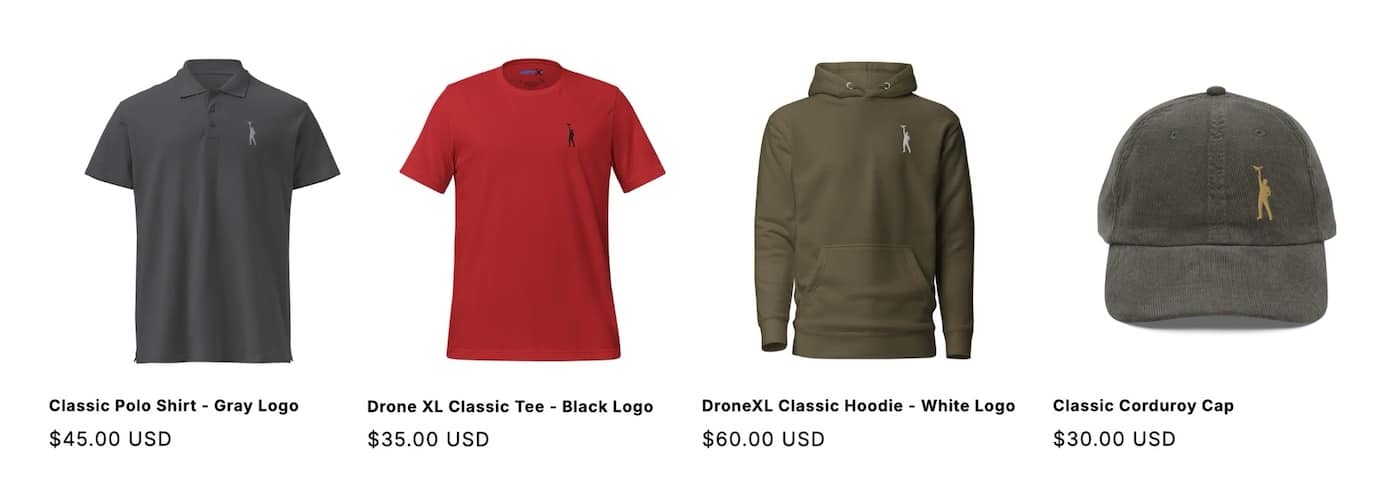

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.