FCC Exempts Blue UAS Drones From Foreign Ban, But the Clock Is Already Ticking

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

I predicted the FCC would need to walk back parts of its sweeping foreign drone ban. Sixteen days after adding all foreign-made drones to the Covered List, the Pentagon has carved out exemptions for Blue UAS platforms and domestically assembled drones. But here’s what the headlines aren’t telling you: these exemptions expire on January 1, 2027, and the real power just shifted to the Department of War.

Here’s what happened:

- What: FCC updated the Covered List to exempt Blue UAS-approved drones and components, plus domestically manufactured products meeting the 65% domestic content threshold

- When: January 7, 2026, via Public Notice DA 26-22

- Who decides: The Department of War (DoW) made the national security determination, not Congress or the FCC

- Expiration: All exemptions terminate January 1, 2027

- DJI and Autel: Still completely blocked from new product authorizations

The FCC received a subsequent National Security Determination from the DoW on January 7, 2026, stating that “UAS and UAS critical components included on Defense Contract Management Agency’s (DCMA’s) Blue UAS list do not currently present unacceptable risks to the national security of the United States.”

According to Reuters, the exempted manufacturers include Parrot, Teledyne FLIR, Neros Technologies, Wingtra, Auterion, ModalAI, Zepher Flight Labs, and AeroVironment. Component suppliers including Nvidia, Panasonic, Sony, Samsung, and ARK Electronics can also continue importing critical parts.

| Category | Status | Expiration |

|---|---|---|

| Blue UAS Cleared List drones/components | Exempt | January 1, 2027 |

| Domestic end products (65%+ US content) | Exempt | January 1, 2027 |

| DJI products (new models) | Blocked | No expiration |

| Autel products (new models) | Blocked | No expiration |

| Previously authorized DJI/Autel models | Legal to sell and use | N/A |

The Pentagon Just Became the Drone Gatekeeper

When the FCC added all foreign drones to the Covered List on December 22, I noted that the escape clause depended entirely on DoW or DHS making specific determinations. That prediction materialized faster than expected, but with a twist that most coverage missed.

The DoW determination includes explicit language that “reliance on any foreign country for critical UAS components still creates significant vulnerabilities for the domestic drone industrial base.” Even while granting exemptions, the Pentagon is signaling these are temporary measures while domestic production scales up.

For Part 107 operators, this means your equipment choices now flow through a Pentagon-controlled approval process. The Blue UAS list, which lost eight vendors in March 2025, becomes the only viable path to new drone purchases unless you’re willing to bet on the “domestic end product” exemption.

The 65% Domestic Content Loophole

The second exemption category creates an interesting pathway that few outlets have analyzed. Under the Buy American Standard (48 CFR 25.101(a)), UAS and components qualify as “domestic end products” if manufactured in the United States with at least 65% domestic content by cost.

This means a drone assembled in Texas using 35% foreign components could theoretically receive FCC authorization. The question becomes whether any manufacturer can actually hit that threshold given current supply chain realities.

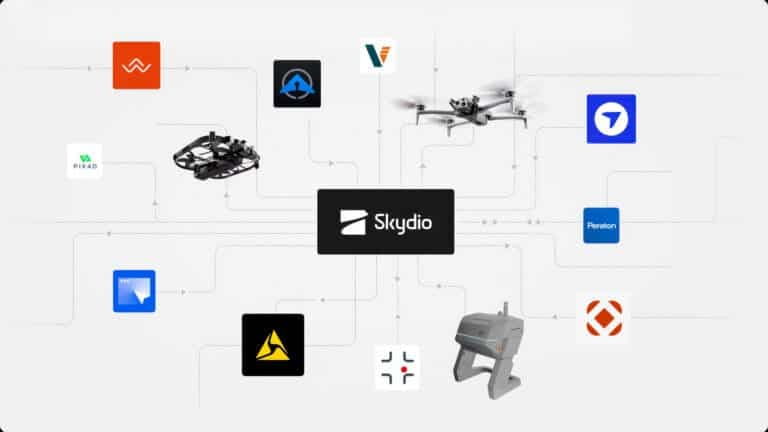

As I reported when the ban first dropped, China produces 99% of the world’s drone batteries. Even Skydio, the flagship American drone company on the Blue UAS list, was rationing parts in October 2024 after a single phone call from Beijing cut off their battery supply. The 65% threshold sounds achievable until you start adding up motor costs, flight controller costs, and camera sensor costs.

There is a potential workaround: solid-state battery startups with 100% domestic intellectual property may qualify as “domestic end products” regardless of where raw lithium is processed. Several California and New York battery companies are reportedly exploring this classification, which could provide a pathway for American drone manufacturers to meet content thresholds sooner than expected.

The DoW determination acknowledges this tension directly: “Industry should use the Buy American standards as a baseline with plans to increase their domestic content requirement.” Translation: 65% is the floor today, but expect that number to climb.

New Exemption Request Process

The FCC also revealed a pathway for manufacturers not currently on the Blue UAS list. Companies can submit requests for “Conditional Approvals” by emailing drones@fcc.gov with required documentation. The FCC will forward these requests to DoW and DHS for evaluation.

Here’s the catch that commercial operators need to understand: according to the guidance, “all entities seeking a waiver for a UAS will be required to establish an onshoring plan for the manufacturing of all UAS critical components, including components that do not require FCC authorization.”

That’s a significant hurdle. Any manufacturer wanting to sell drones in America must now demonstrate a credible plan to eventually manufacture everything domestically, including motors, batteries, and flight controllers that never needed FCC approval in the first place.

The upside: internal guidance suggests DoW and DHS are targeting a 45-day turnaround for Conditional Approval reviews. That’s potentially faster than the traditional FCC equipment authorization process, which could benefit manufacturers willing to commit to onshoring roadmaps.

What This Means for DJI and Autel

Nothing changes for Chinese manufacturers. The exemptions apply only to Blue UAS-listed products and domestically assembled drones. DJI and Autel remain completely blocked from receiving new FCC equipment authorizations.

When DJI responded to the original ban, a spokesperson said concerns about data security “have not been grounded in evidence and instead reflect protectionism.” Today’s exemption for competitors while maintaining the block on Chinese manufacturers will likely reinforce that argument.

The critical distinction remains unchanged from my December 24 analysis: existing DJI models already authorized by the FCC can still be imported, sold, and used. The Air 3S, Mini 4 Pro, Mavic 3 series, and Matrice lineup remain legal. Only future DJI products are blocked.

The January 2027 Deadline

Perhaps the most significant detail buried in the DoW determination is the explicit sunset clause: “This determination will terminate on January 1, 2027 unless superseded by a newer national security determination.”

The Pentagon is creating a one-year window for the American drone industry to demonstrate it can scale domestic production. The determination explicitly states: “This determination will terminate on January 1, 2027, and shall be reassessed prior to its termination to assess how much the domestic content required should increase to meet this goal.”

There are two ways to read this deadline. The pessimistic view: it’s a cliff that creates planning chaos, since departments can’t commit to long-term contracts when regulatory status expires in 12 months. The optimistic view: it’s a forcing function that prevents companies from indefinitely assembling foreign components under a “Made in USA” label without actually investing in domestic manufacturing.

For Part 107 operators making equipment decisions, both interpretations matter. A drone you purchase in mid-2026 could face parts availability challenges if exemptions aren’t renewed. But if domestic production scales as intended, the supply chain could actually stabilize rather than contract.

DroneXL’s Take

We’ve been tracking the FCC’s foreign drone restrictions since the October 2025 vote gave the agency retroactive enforcement powers. Today’s exemption is exactly what I predicted would happen: the administration walked into a policy it couldn’t fully enforce without destroying the drone industry, and now they’re carving out exceptions to make it workable.

I’ll give credit where it’s due: the 65% domestic content rule actually provides a legal framework for “Made in USA” drones to exist even while using global supply chains for non-critical parts. Without this exemption, the December ban would have been a total market freeze. And by using the Blue UAS list as the benchmark, the government is finally unifying military and commercial security standards, which reduces the compliance burden for American startups that previously navigated different rules for different agencies.

The optimistic read on the January 2027 deadline is that it’s a checkpoint, not a cliff. It serves as a forcing function to ensure companies don’t just assemble Chinese kits in the US indefinitely but actually invest in domestic motor and battery manufacturing. That’s a legitimate policy goal.

But here’s where I remain skeptical: this framework still picks winners and losers. Blue UAS companies, many of which already have government contracts and lobbying relationships, get a one-year competitive runway. DJI and Autel, which serve the vast majority of commercial and recreational pilots, remain locked out with no pathway to compliance regardless of what security measures they might implement.

Here’s what I expect: Blue UAS manufacturers will use this year to lobby for permanent exemptions while arguing they can’t meet higher domestic content thresholds. The 65% requirement will quietly get extended or maintained. And by December 2026, we’ll be having a conversation about whether to extend exemptions again, because building domestic battery and motor production takes longer than twelve months.

The January 2027 deadline creates planning challenges for departments evaluating fleet purchases. You can’t commit to long-term contracts when regulatory status expires in 12 months. But the alternative interpretation is that this deadline forces urgency on domestic manufacturing investments that might otherwise be delayed indefinitely.

For Part 107 operators, my advice is unchanged from December: if you need new equipment in 2026, Blue UAS platforms are now your safest bet. But factor the January 2027 deadline into your planning. The rules could change again in twelve months, though the direction of travel seems clear: more domestic content requirements, not fewer.

What do you think about the Pentagon controlling which drones Americans can buy? Does the one-year exemption provide enough certainty for your operations? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.