Why the “Pain” of a DJI Drone Ban Means Lives Lost, Not Just Lost Profits

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

In a recent Bloomberg Opinion piece, columnist Thomas Black argues that the forced transition from Chinese-made drones to American alternatives is a “necessary pain” required to secure our national supply chain. He frames this transition as a messy spreadsheet calculation, a temporary economic pinch that will eventually balance itself out as U.S. manufacturing wakes from its slumber.

I agree with his diagnosis: dependency on a strategic rival for critical technology is a vulnerability. But I vehemently disagree with his prescription.

To treat this transition as merely an economic hurdle is to ignore the operational reality of public safety in America. The “pain” Black refers to isn’t just about quarterly earnings or stock prices; it is quantifiable in missing persons not found, fires burning longer, and small businesses shuttering.

We need to ask the hard question: Is the pain justified, and can we survive the surgery?

When “Pain” Means Body Bags

The Bloomberg piece discusses the ban’s impact in abstract terms: market disruption, supply chain adjustments, economic transition costs. But here’s what “pain” looks like in operational reality.

Imagine a search and rescue operation in the mountains of Utah. A hiker goes missing as darkness falls and temperatures drop below freezing. Today, a local volunteer search and rescue team deploys a DJI Mavic 3 Thermal (M3T). It costs roughly $5,500, covers 200 acres per hour, and can detect a heat signature through dense canopy. They locate the victim within 90 minutes. The hiker survives.

Now imagine that same scenario in 2026.

The department’s Chinese fleet has been grounded. The American-made alternative they were promised? It costs $15,000 to $20,000, three times the price. It has 25 minutes of battery life compared to the Mavic’s 45 minutes, forcing frequent returns to base that break the search grid. Because the department operates on a fixed grant budget, they could only afford one drone instead of three. The search takes six hours instead of 90 minutes. The hiker doesn’t make it.

This isn’t fear-mongering. It’s basic operational math. If you triple the cost of hardware for fixed-budget agencies, you cut their fleet capability by 66% overnight. That capability gap is measured in lives.

The Scale of the Problem

DJI’s Drone Rescue Map has documented over 1,054 lives saved globally by drones hikers found in freezing temperatures, drowning victims spotted in surf, Alzheimer’s patients located in dense woods. If we reduce the U.S. public safety fleet size by 66% due to cost, we are statistically guaranteeing that hundreds of searchable incidents will go without aerial support. The “pain” is not a line item on a budget spreadsheet; it’s a hypothermic victim not found because the county’s one compliant drone was deployed on a call 30 miles away.

Florida DJI Drone Ban: The Canary in the Coal Mine

We don’t have to hypothesize about these impacts. Florida has already lived through this transition, and the results are sobering.

When Florida effectively banned drones from “countries of concern” for state agencies, the fallout was immediate and expensive:

- The state estimated it would cost $200 million to replace the grounded Chinese drones

- The legislature set aside just $25 million for the transition, a $175 million shortfall that left departments scrambling

- Agencies like the Orange County Sheriff’s Office were forced to spend nearly $580,000 just to replace 18 drones

Many smaller departments didn’t have an extra half-million dollars lying around. They simply grounded their fleets. They went from having a “bird in the air” to having nothing. That is a net loss in public safety capability that no amount of “Buy American” rhetoric can fix in the short term.

This is what “pain” looks like when it moves from policy paper to patrol car.

Fire Service Operations: Drones have become indispensable tools for fire departments, providing real-time thermal imaging to identify hotspots, monitoring structural integrity before sending personnel inside, and maintaining aerial awareness of wildfire perimeters. They keep firefighters out of harm’s way while improving operational effectiveness.

The Los Angeles Fire Department operates multiple DJI drones across its stations. New York City Fire Department has invested heavily in drone capabilities. These aren’t luxury items, they’re life-safety equipment that has fundamentally changed how departments operate.

When these drones can no longer be maintained, when replacement parts dry up, when manufacturer support vanishes, departments face a choice: ground their capability entirely or continue operating degraded equipment. Neither option is acceptable when lives are on the line.

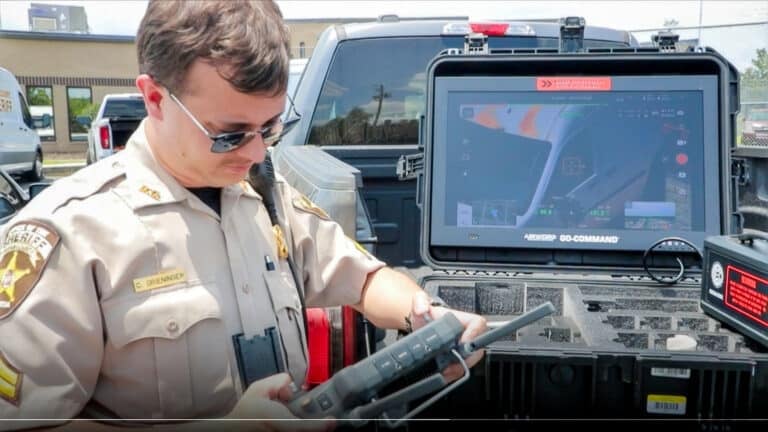

Law Enforcement and Tactical Response: SWAT teams use drones to assess hostage situations, reducing risk to both officers and civilians. Police departments use them for accident reconstruction, keeping officers out of active traffic lanes. They document crime scenes from angles that would otherwise require expensive helicopter time.

The “pain” of losing this capability isn’t just operational inconvenience. It’s officers exposed to unnecessary risk. It’s longer scene processing times. It’s reduced situational awareness in critical moments.

The Budget Reality for Volunteer Departments

The impact will be most severe precisely where drone capability matters most: rural and volunteer fire departments, and volunteer search and rescue teams operating on shoestring budgets.

These organizations don’t have the luxury of “finding room in the budget.” A rural volunteer fire department in Montana operating on $50,000 annually from bake sales, fundraisers, and small municipal grants cannot suddenly find an extra $15,000 for a single drone to replace the three DJI Mavic 3Ts they purchased for $16,500 total.

The math is brutal and binary: either they lose aerial thermal capability entirely, or they divert funds from other critical needs like turnout gear, training, or vehicle maintenance. Most will simply ground their drones and return to operating the way they did in 2015, except now their communities have come to depend on that aerial capability for missing person searches and structure fire operations.

Volunteer search and rescue teams face the same impossible choice. These are unpaid civilians who already donate thousands of hours annually and often purchase their own equipment. Asking them to collectively fundraise an additional $45,000 to replace a three-drone DJI fleet with a single American alternative means that capability simply disappears.

The result is predictable: America’s public safety drone fleet will shrink dramatically not because agencies choose to give up capability, but because they literally cannot afford to maintain it. The ban doesn’t force a one-to-one replacement, it forces a three-to-one reduction in deployed assets. We’re not transitioning the fleet; we’re decimating it.

The Devastation of Drone Service Providers

Beyond public safety, there are thousands of small businesses built on DJI’s technology platform. These aren’t hobbyists, they’re licensed Part 107 commercial operators or drone Service Providers running legitimate businesses:

- Real estate photographers who’ve invested $15,000-30,000 in equipment, built client relationships, and created sustainable income streams

- Construction site monitoring services providing daily progress documentation to project managers

- Infrastructure inspection companies checking cell towers, bridges, and power lines without putting workers at height

- Agricultural services providing crop health analysis and precision spraying guidance

- Wedding and event videographers who’ve made drone footage a standard offering

Each of these operators faces the same brutal calculus: their DJI equipment will become increasingly unsupportable as parts dry up and firmware updates cease. American alternatives either don’t exist at comparable price points or lack the feature sets their clients expect.

According to the Drone Advocacy Alliance, 67% of small drone businesses report they would be forced to close if a total DJI ban were implemented immediately. These businesses operate on thin margins. They cannot triple their capital expenditure to buy a Blue sUAS drone that, in many cases, offers inferior resolution or software features for their specific workflows.

The Bloomberg piece acknowledges this pain exists but frames it as acceptable collateral damage in service of larger strategic goals. But we’re talking about real people who made legitimate business investments based on legally available technology, who now face financial ruin through no fault of their own.

How many thousands of small businesses is it acceptable to destroy? What’s the number where “necessary pain” becomes “unacceptable devastation“?

The Fatal Flaw: The “Sleeping Giant” Myth

The central assumption underlying the “necessary pain” argument is that American manufacturers are a sleeping giant, waiting for a captive market to unleash their innovation. Give them protection from Chinese competition, the thinking goes, and American ingenuity will rush in to fill the void. Economics 101.

Except the drone industry is littered with the wreckages of well-funded American companies that tried to beat DJI and failed, not because of politics or lack of patriotism, but because of the immense difficulty of the technology itself.

The GoPro Karma Disaster

In 2016, GoPro, a company with hundreds of millions in revenue, strong brand recognition, and deep expertise in action cameras, launched the Karma drone. They had resources, talent, and a built-in customer base of action sports enthusiasts who already trusted the brand.

The Karma was a disaster. Initial units were plagued by technical failures, with drones literally falling out of the sky due to battery connection flaws. GoPro recalled every unit sold, took a massive financial hit, and eventually discontinued the product line entirely in 2018. They were obliterated by the release of the DJI Mavic Pro, which was smaller, smarter, and more reliable.

This wasn’t because GoPro lacked commitment or resources. It was because competing with DJI’s technological lead and manufacturing scale is extraordinarily difficult, even for established players with deep pockets.

Sony’s Expensive Failure

If anyone had the resources and technical capability to challenge DJI, it should have been Sony. The electronics giant launched the Airpeak S1 in 2021, positioned as a professional cinematography platform.

The Airpeak was technologically impressive, capable of carrying Sony’s mirrorless cameras, featuring advanced stabilization, with legitimate professional applications. It was also $9,000 for just the drone, possessed a shockingly short battery life, and total system costs easily exceeded $15,000.

Despite Sony’s engineering prowess, manufacturing capability, and deep pockets, the Airpeak never gained meaningful market traction. The combination of extreme cost and narrowly defined use cases meant it couldn’t compete with DJI’s ecosystem breadth and value proposition. Sony recently discontinued the product.

Sony didn’t fail because they built a bad product. They failed because DJI’s decade-long head start, vertical integration, and economies of scale created a competitive moat that even Sony, the master of imaging technology, couldn’t bridge.

If Sony and GoPro, companies with deep supply chains and world-class engineering, could not “wake the giant,” why do we assume that startups with a fraction of their capital can do it overnight?

Skydio’s Strategic Retreat

Perhaps most tellingly, Skydio, widely considered America’s best hope for competing with DJI, has effectively conceded the consumer and commercial markets entirely.

Skydio initially launched with the ambitious goal of challenging DJI across all segments. Their autonomy technology was genuinely impressive, with obstacle avoidance capabilities that in some ways exceeded DJI’s offerings. The Skydio 2 was a technological achievement that earned genuine respect in the industry.

But by 2024, Skydio had pivoted almost entirely away from consumer and general commercial markets to focus exclusively on government contracts and public safety agencies. The company discontinued the Skydio 2+ for consumer purchase and now concentrates on the X10 and X2 platforms designed specifically for defense and first responder applications.

This wasn’t a choice born of preference, it was a tacit admission that competing with DJI on price and features in open markets is nearly impossible. Even with significant venture capital backing, cutting-edge autonomy technology, and “Made in America” appeal, Skydio couldn’t make the economics work for consumer drones priced against the Mavic series.

The company found its viable niche in government procurement where “Blue sUAS” compliance and data security concerns justify premium pricing. But this retreat to protected markets is precisely the problem: American manufacturers can survive when competition is eliminated by regulation, but they struggle to compete on merit in open markets.

If Skydio, with its technological advantages, strong leadership, and substantial funding, had to abandon the broader market to survive, what does that tell us about the readiness of the American drone industry to suddenly replace DJI across all sectors?

The Three-Year Gap (At Minimum)

Perhaps the most sobering assessment comes from someone actually trying to build American drones. Blake Resnick, founder and CEO of BRINC Drones, is one of the brightest minds in the U.S. drone space, leading a company that builds excellent SWAT-specific drones including the LEMUR series. BRINC is one of the American companies that’s supposed to fill the void left by DJI.

Speaking on the PiXL Drone Show in May, 2024, Resnick was remarkably candid about the challenge his company faces. Even with unlimited resources, unlimited capital, unlimited access to talent, unlimited manufacturing capacity, BRINC would need at least three more years to catch up to DJI’s current technological capabilities. And that’s assuming they actually could bridge the gap at all, which Resnick acknowledged isn’t guaranteed.

Let that sink in. A leading American drone manufacturer, one of the companies with the best shot at competing with DJI, says they’re a minimum of three years away from parity even under ideal conditions.

The DJI ban takes effect on December 23, 2025, just over one month away. We’re forcing a market transition years before domestic alternatives will be ready. We are jumping off a cliff and hoping to knit a parachute on the way down.

And here’s the kicker: DJI isn’t standing still. By the time U.S. manufacturers catch up to the Mavic 3 Enterprise, DJI will likely be on the DJI Mavic 5 or 6, with further technological advances that widen the gap again.

The Capability Chasm

It’s not just about time to market. It’s about the specific capability gaps that make direct replacement impossible in the near term.

Battery Technology: DJI’s drones achieve flight times of 40-46 minutes for prosumer models like the Mavic 3 series. Most American alternatives offer 20-30 minutes. That’s not a minor difference, it’s the difference between completing a mission and having to return to base for a battery swap, doubling operational time.

Obstacle Avoidance: DJI’s omnidirectional obstacle sensing has become table stakes for professional operations, especially in complex environments like urban areas, forests, or industrial sites. Many American alternatives have limited or no obstacle avoidance, dramatically increasing crash risk and operator stress.

Camera and Payload Systems: DJI’s integration of high-quality cameras, mechanical shutters, and advanced image processing represents years of development. The Mavic 3T’s thermal camera system, for instance, provides resolution and temperature accuracy that rivals dedicated thermal imaging equipment costing tens of thousands of dollars. American alternatives either lack thermal capability entirely or offer significantly degraded performance.

Software Ecosystem: DJI’s flight planning software, photogrammetry tools, and third-party integration represent an ecosystem built over more than a decade. New entrants can’t simply replicate this with a competent engineering team and adequate funding. It requires iteration, user feedback, and time.

Price Point: Perhaps most importantly, DJI achieved all of this at consumer and prosumer price points. The Mavic 3 Enterprise costs around $5,000-7,000 depending on configuration. American alternatives with even 70% of the capability routinely cost $10,000-15,000 or more.

For cash-strapped municipal fire departments, small police agencies, and volunteer search and rescue organizations, that price differential isn’t merely inconvenient, it’s prohibitive.

The Security Argument: Valid But Incomplete

None of this is to dismiss the legitimate national security concerns that motivated the ban. The arguments have genuine merit:

Data Security: DJI drones transmit flight data, imagery, and telemetry that could theoretically be accessed by Chinese authorities. For operations near critical infrastructure or military installations, this represents a genuine vulnerability.

Supply Chain Reliability: Dependence on Chinese manufacturing for critical emergency response equipment creates strategic vulnerability. If U.S.-China relations deteriorate further, access to parts, firmware updates, and support could be weaponized.

Air Traffic Management: As the FAA moves toward beyond-visual-line-of-sight (BVLOS) operations, the integration of drones into the National Airspace System creates potential attack surfaces. Chinese-manufactured drones operating at scale could theoretically be exploited to disrupt aviation safety.

Industrial Policy: More broadly, allowing Chinese companies to dominate a strategic technology sector through subsidized competition does create long-term competitiveness concerns for American industry.

These are all valid points. The question isn’t whether the concerns are real, they are. The question is whether the chosen solution matches the problem’s actual contours.

Alternative Approaches That Could Actually Work

The fatal flaw in the current approach is the cliff-edge timeline. We’re mandating a transition before the prerequisites for success exist. But alternative approaches could have addressed security concerns while providing time for domestic industry to mature.

1. The “Solar Panel” Model: Tariffs Fund Subsidies

Instead of an outright ban, implement a 100% tariff on Chinese drones and use that revenue to directly subsidize the purchase of American Blue sUAS drones for police, fire, and search and rescue departments.

This artificially lowers the price of U.S. drones to match DJI’s pricing, allowing American manufacturers to scale up volume naturally without bankrupting local agencies. It’s protectionism with a safety net, the same approach used successfully to build domestic solar panel manufacturing.

Key advantage: Addresses security concerns while eliminating the capability gap for life-safety applications.

2. Security-Hardened Chinese Drones as Bridge Technology

Rather than an outright ban, require certification that Chinese drones meet specific security standards:

- Firmware auditing: Independent security firms validate that drone firmware contains no data exfiltration or remote access capabilities

- Air-gapped operation: Mandate “Local Data Mode” for all non-sensitive operations, with internet connectivity permanently disabled

- Hardware inspection: Physical examination to ensure no unauthorized components

- Geo-fencing: Drones must automatically prevent operation within defined distances of sensitive sites

This approach acknowledges that Chinese drones currently provide the best capability-to-cost ratio while implementing meaningful security safeguards during the transition period.

Key advantage: Neutralizes the data security threat immediately without sacrificing operational capability.

3. Graduated Transition Timeline

Instead of a blanket December 23, 2025 ban, implement tiered restrictions:

- Immediate (2025): Ban DJI/Autel for federal government use, critical infrastructure monitoring, and military contractor operations

- Phase 2 (2027): Extend ban to state/local government agencies, but with generous federal subsidies for replacement American-made equipment

- Phase 3 (2029): Extend ban to commercial operations in sensitive sectors (utilities, telecommunications, transportation infrastructure)

- Phase 4 (2031): Complete ban on new DJI/Autel sales, with existing equipment allowed to operate under security protocols

This approach addresses the most critical security vulnerabilities immediately while providing realistic time for the market to develop alternatives.

Key advantage: Matches transition timeline to actual manufacturing capability development, not wishful thinking.

Conclusion: A Transition, Not an Amputation

The Bloomberg piece asks whether the “pain” of the DJI ban is justified. But it treats pain as an acceptable abstraction in service of larger strategic goals.

The reality is that “pain” in this context means:

- Search and rescue operations that take hours instead of minutes, with lives lost in the gap

- Fire departments operating without critical thermal imaging capability that keeps firefighters safe

- Police officers exposed to unnecessary risk at accident scenes

- 67% of small drone businesses facing closure, thousands of legitimate enterprises destroyed

- A three-to-five-year capability gap even under best-case scenarios

- Tens of billions in opportunity costs from delayed drone integration into critical infrastructure

Is that pain “necessary”? That depends on whether we believe the current timeline and structure are the only way to achieve legitimate security objectives.

The strategic case for domestic drone manufacturing capability is sound. The security concerns about Chinese technology in critical systems are legitimate. The goal of reducing dependence on Chinese manufacturing in strategic sectors is reasonable.

But the execution is deeply flawed.

GoPro tried and failed. Sony tried and failed. Skydio tried and failed. Blake Resnick, actually building American drones, says even with unlimited resources, his company needs at least three more years to catch up, assuming they can at all.

We need American drones. But until American manufacturers can produce viable, affordable, volume-manufactured alternatives, banning the tools that save lives is not a strategy, it’s a self-inflicted wound.

The path forward requires honesty about timelines and costs:

- Use tariff revenue to subsidize American drones for first responders, achieving price parity with Chinese alternatives

- Implement security protocols (air-gapped operation, firmware auditing) for Chinese drones in non-sensitive applications during the transition

- Create a graduated restriction timeline that addresses immediate security concerns while allowing realistic time for capability development

- Acknowledge that forcing a transition before alternatives exist doesn’t protect national security, it just creates operational gaps that put Americans at risk

The question isn’t whether we should have American drone manufacturing capability, we absolutely should. The question is whether the current approach represents thoughtful policy design or security theater combined with unfounded optimism about American competitiveness.

The Bloomberg columnist argues the pain is justified. I’d argue we haven’t honestly calculated what the pain will be, how long it will last, or whether better approaches could achieve the same objectives with far lower costs.

That’s a conversation worth having before December 23, 2025, not after.

Because behind the abstraction of “economic transition costs” are real firefighters, real search and rescue volunteers, real small business owners, and real people whose lives depend on these tools working when they’re needed most.

What do you think? Is the current transition timeline realistic, or should we acknowledge the capability gap and adjust our approach? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Disclosure: DroneXL.co has relationships with drone manufacturers including DJI (DJI sends us drones for review purposes. The DJI Affiliate program effectively seized to exist years ago. We have never received payment from DJI for an article, including this one.) This article and analysis represents the author’s independent assessment of the policy implications of the upcoming ban.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.