American Drone Hobby Faces Accessibility Crisis as Bans, Regulations, and Market Forces Converge

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

The United States drone hobby is under severe pressure from multiple directions simultaneously, threatening to transform the most accessible entry point into aviation into an increasingly expensive and restricted pursuit. While Canadian and European enthusiasts enjoy flourishing drone communities with sensible regulations, U.S. hobbyists face an impending manufacturer authorization freeze, abandoned consumer markets, and regulatory burdens that risk pushing newcomers away from modern aviation technology entirely.

This isn’t abstract policy debate. In Switzerland and across the U.S., rubber band-powered free-flight aircraft clubs still exist—enthusiasts flying uncontrolled balsa wood planes powered by twisted rubber strips, launching them into the air with no ability to steer or recover them. These aircraft, dating back to Alphonse Pénaud’s 1871 Planophore, represent some of the most primitive forms of model aviation. They’re a fascinating historical hobby—but they’re also a reminder of what happens when electronic aviation becomes inaccessible to ordinary people.

Note: There is a Flite Fest 2023 photo gallery at the end of the article.

Why This Matters: The Aviation Talent Pipeline at Risk

The mounting barriers to drone accessibility aren’t just about recreation. They’re about the future of American aviation itself. Young people who grow up flying DJI Mini or Ryze Tello drones in their backyards aren’t just hobbyists—they’re tomorrow’s commercial pilots, aerospace engineers, UAV operators, and defense contractors. High school drone programs across the country teach coding, FAA regulations, project management, and aeronautical concepts through accessible consumer drones. When you make these aircraft harder to obtain or more complicated to operate legally, you don’t just hurt a hobby—you constrict a critical talent pipeline at exactly the moment when young soldiers are demonstrating unprecedented aptitude for drone systems.

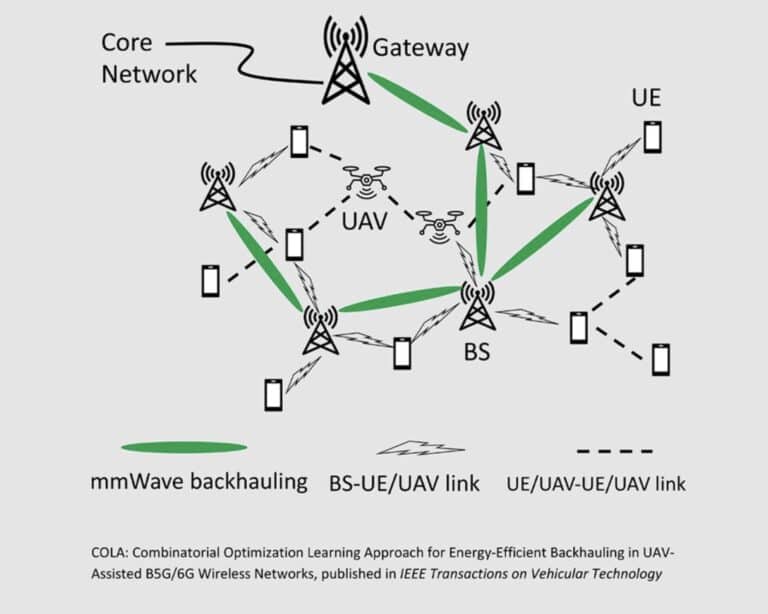

Military officials have noted that soldiers with STEM backgrounds from drone-friendly schools master complex UAV systems in under eight hours. The hobby-grade drones that sparked their interest in aviation create real national security value—just not the kind that benefits lobbyists and defense contractors who want to eliminate consumer competition.

The December Authorization Deadline and Market Scarcity

DJI faces an automatic December 23, 2025 deadline for adding the company to the FCC’s Covered List unless a federal agency completes a mandated security review—and as of late October 2025, no agency has confirmed they’re conducting one. This statutory deadline would block new DJI products from receiving FCC equipment authorizations, effectively ending new drone sales in the United States.

To be clear: existing DJI drones remain legal to fly. This isn’t a usage ban or a requirement to ground current fleets. But the impact on accessibility is already severe. As of June 2025, DJI’s U.S. inventory shows near-total stock depletion across their entire lineup—from the budget-friendly Neo to the cinematic Inspire 3. The company controls 90% of the consumer market and 70% of the commercial sector, meaning tens of thousands of American pilots face a future where replacement drones, spare parts, warranty, and firmware updates become increasingly scarce.

DJI attempted to circumvent anticipated restrictions through proxy companies like Skyany, Skyrover, and Cogito, but an October 28 FCC vote targeted these shell operations through component parts restrictions. The workarounds appear unlikely to survive regulatory scrutiny. If the December deadline passes without an audit, new DJI drones become illegal to authorize for sale—and the existing supply is already running dry.

The practical effect is straightforward: aspiring drone pilots in 2026 and beyond will face a dramatically constrained market where the most affordable, capable consumer drones are no longer available new. Schools planning to start drone programs will struggle to find equipment. Young people discovering aviation will encounter barriers their Canadian and European counterparts don’t face.

Existing DJI aircraft won’t be “bricked” or fall from the sky—that’s a myth that drone dealers have debunked. But firmware updates will likely stop, replacement parts will become scarce, and warranty support will evaporate. Used market prices are already inflating. This is a slow constriction, not an instant collapse, but the trajectory is clear.

American Manufacturers Abandon the Consumer Market

Here’s where the accessibility crisis deepens: U.S. drone manufacturers aren’t stepping up to fill the void at consumer price points. They’re walking away from that market entirely.

Skydio quit the consumer market in August 2023, announcing they would “sunset our consumer drone offerings and shift our focus to exclusively serve enterprise and public sector consumers.” The company couldn’t compete with DJI on price or features—customers faced wait times up to a year—so instead of improving their products, Skydio pivoted to aggressive lobbying for legislative restrictions on Chinese manufacturers.

Let that sink in. Rather than building better consumer drones, Skydio chose to legislate their competition out of the market. Industry professionals have been vocal about this approach, with one search-and-rescue coordinator stating that Skydio is “actively destroying the U.S. drone industry” through their connections to Representative Elise Stefanik, the primary architect of the authorization ban legislation.

Other U.S. manufacturers like BRINC Drones focus exclusively on defense and public safety applications—$10,000+ aircraft that are completely out of reach for hobbyists, students, or aspiring commercial pilots. These companies aren’t interested in selling $500 drones to teenagers at the park. There’s no money in that market compared to government contracts.

The Regulatory Burden: Remote ID and Compliance Complexity

Even with drones still available and legal to fly, U.S. regulations create barriers that don’t exist in other countries. Remote ID requirements that took effect in March 2024 mandate that most drones over 0.55 pounds (250 grams) broadcast identification and location data during flight.

For drones without built-in Remote ID, pilots must purchase add-on modules costing between $89 and $327. These modules add between 1.5 grams and 32 grams of weight—enough to push a sub-250-gram drone over the registration threshold, creating a catch-22 where compliance makes you non-compliant.

The alternative is flying in FAA-Recognized Identification Areas (FRIAs). The good news is that FRIA availability has expanded significantly—approximately 1,900 AMA-associated sites plus hundreds more from other community-based organizations and educational institutions now provide Remote ID-exempt flying locations. This is substantially more access than early projections suggested.

However, FRIA distribution remains uneven geographically, and the requirement that both drone and pilot stay within boundaries with maintained visual line of sight still represents a meaningful constraint compared to pre-Remote ID flying freedom. For urban pilots or those in less-populated states, reaching a FRIA may still require significant travel.

The underlying principle remains sound—aircraft identification helps integrate drones into national airspace safely. But the implementation creates cost, weight, and operational barriers that other countries have avoided through more flexible frameworks.

Alternative Manufacturers Exist—But Haven’t Solved the Gap

Yes, other consumer drone manufacturers exist and continue working on products. Autel Robotics launched their Nano series in 2021 as a sub-250-gram competitor to DJI’s Mini line, priced at $649 to $949. But the company’s consumer product cadence has slowed considerably since then, and they haven’t matched DJI’s pace of innovation or price competitiveness.

The Insta360-backed Antigravity A1, set to launch later this year or early 2026, represents genuine innovation with its 8K 360-degree capture system at 249 grams. It demonstrates that consumer drone innovation can happen without it being another DJI drone. Other manufacturers continue developing products, and some target specific niches effectively.

But here’s the reality: these alternatives haven’t filled the consumer accessibility gap that DJI created. The Chinese manufacturer’s vertical integration, manufacturing scale, and R&D investment have created technological and price advantages that take years to match. When your motors cost $2 to manufacture and competitors pay $10, when you produce components in-house while others rely on supply chains, you create barriers that don’t disappear because Congress passed a law.

For a fifteen-year-old with $500 saved from mowing lawns, the market in 2026 will offer dramatically fewer options than it did in 2024. That matters for hobby accessibility and aviation pipeline development.

The FPV Alternative: A Higher Barrier to Entry

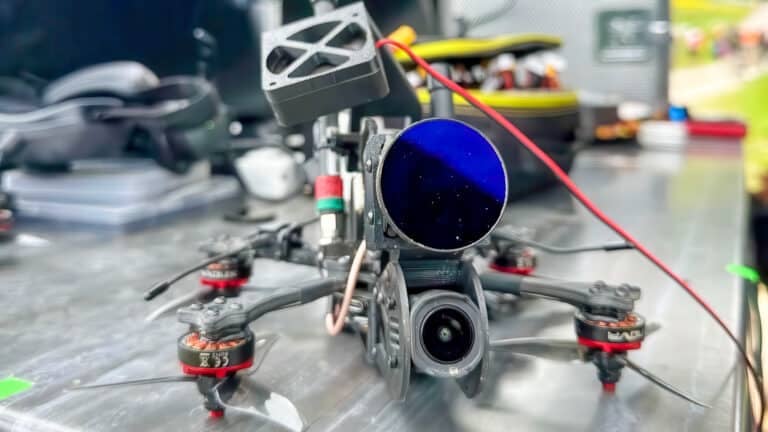

Some argue that aspiring pilots can simply build their own FPV (First Person View) drones using off-the-shelf components. While the FPV community is vibrant, welcoming, and technically sophisticated, this path requires expertise that excludes most potential hobbyists—especially young people just discovering aviation.

Building a custom FPV drone means soldering electronic speed controllers, programming flight controllers, configuring radio systems, and understanding PID tuning. Learning to fly in manual mode requires extensive simulator practice—at least 4-5 hours before you can maintain stable hover—and mastering throttle control that experienced pilots describe as “your nightmare for the first few weeks.”

For enthusiasts willing to invest that time and develop those skills, FPV flying is incredibly rewarding. But it represents a fundamentally different barrier to entry than ready-to-fly consumer drones. The genius of the DJI Mini series was its simplicity: take it out of the box, charge the battery, and fly. No soldering. No programming. No simulator time. Just immediate access to the magic of flight.

That low barrier to entry is what hooks ten-year-olds who grow up to become aerospace engineers. Raising the difficulty threshold means fewer people ever enter the aviation pipeline.

How Other Countries Got It Right

The contrast with other countries is stark. Canadian drone enthusiasts enjoy full access to DJI’s product lineup without stock shortages, security theater, or artificial market restrictions. The same drones flying in Toronto are somehow national security threats in Tampa.

European Union countries have implemented common-sense weight-based regulations through EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) that provide manufacturing tolerances and clear compliance pathways. The EU allows a ±3% weight variance during manufacturer certification, recognizing that real-world manufacturing has tolerances. The FAA provides no such accommodation—if your drone measures 250.1 grams, you’re in violation.

Europe also implements risk-based categories that scale regulations to actual danger rather than treating every small drone as an equivalent threat. A 249-gram camera drone isn’t subject to the same restrictions as a 25-kilogram industrial platform. This proportionate approach encourages hobby participation while maintaining safety.

The result? Thriving drone communities, robust STEM education programs using accessible aircraft, and talent pipelines that feed commercial and defense sectors. These countries aren’t sacrificing security—they’re just not sacrificing their aviation futures to protectionist politics.

What Remains Legal (And What’s At Risk)

It’s crucial to understand what current U.S. policy does and doesn’t restrict:

Still Legal:

- Flying existing DJI drones (no usage ban exists or is proposed)

- Buying used DJI equipment (secondary market remains active)

- Operating drones with Remote ID compliance (built-in, modules, or in FRIAs)

- Flying sub-250-gram drones recreationally (no registration/Remote ID required)

- Commercial operations with current equipment (Part 107 operations continue)

At Risk After December 23, 2025 (If No Audit Occurs):

- New DJI drone sales/authorizations (would be blocked)

- Firmware updates and official support (likely discontinued)

- Spare parts availability (will become scarce)

- Warranty service (will end for new issues)

- Market competition that keeps prices accessible

The December deadline doesn’t ground existing fleets, but it does freeze the market in place while supply constraints gradually worsen. For current drone owners, operations continue. For future pilots, the barriers to entry rise significantly.

DroneXL’s Take

We’ve been covering the mounting pressure on American drone policy for years, and it’s reached a critical juncture. Skydio’s pivot from consumer products to legislative lobbying revealed what this fight is really about: not data security, but market protection for companies that can’t compete on merit. When industry experts warned that U.S. lawmakers are pushing to eliminate Chinese drones while no American alternative exists at consumer prices, they were dismissed.

The political machinery behind these restrictions is well-documented. Representative Elise Stefanik’s December 2024 NDAA provision didn’t emerge from intelligence briefings—it emerged from lobbying apparatus. Senator Rick Scott’s October 2025 emergency letter to the FCC demanding retroactive equipment revocations wasn’t about protecting Americans—it was about eliminating competition before the automatic deadline even triggers.

Yes, the federal government has also signaled goals around UAS commercialization and integration into national airspace. These competing policy objectives create uncertainty rather than clarity. But the immediate reality facing hobbyists is unambiguous: market access is constricting, costs are rising, and regulatory complexity is increasing.

This is protectionism masquerading as security policy. If DJI drones were genuinely dangerous, why do 88% of New York state and local agencies use them? Why do farmers, firefighters, and search-and-rescue crews depend on them? Why haven’t multiple security audits found evidence of data exfiltration when operating in local mode?

The answer: DJI makes the best consumer drones at accessible prices, and American manufacturers would rather eliminate that competition than match it.

But here’s what gets lost in political maneuvering: real human costs. The fifteen-year-old in rural Montana who dreams of becoming a commercial drone pilot but faces a market with fewer affordable options. The high school STEM program that can’t replace aging equipment with anything comparable at budget-friendly prices. The hobbyist who’s flown responsibly for a decade and suddenly faces equipment scarcity through no fault of their own.

When we make aviation harder to access, we don’t just hurt hobbyists. We damage national competitiveness. China isn’t restricting DJI—they’re using consumer drones to create the world’s largest pool of UAV-literate citizens. Europe isn’t limiting access—they’re building regulatory frameworks that encourage safe adoption. Canada isn’t choosing protectionism—they’re letting their citizens develop skills that feed commercial and defense sectors.

The United States appears to be choosing differently. Rather than matching Chinese manufacturing capability or European regulatory sophistication, we’re allowing lobbying pressure to drive policy that constricts hobby accessibility without producing viable consumer alternatives.

Policy outcomes aren’t predetermined. The mandated security audit could still be completed before December 23. The timeline could be extended. Alternative manufacturers could surprise us with competitive consumer products. Federal integration goals could override protectionist impulses. These possibilities exist.

But the trajectory right now points toward reduced accessibility, higher barriers to entry, and a weaker aviation talent pipeline. That’s not inevitable—it’s a choice being made through legislative action and regulatory pressure, one deadline and one FCC vote at a time.

The Swiss rubber band aircraft hobby exists because it’s beautiful, challenging, and historically significant. But it would be tragic if American young people in 2030 face significantly constrained access to modern drone technology not because the technology failed, but because policy choices made in 2024-2025 prioritized political considerations over aviation accessibility.

There are solutions. Complete the security audit on time. Implement EU-style proportionate regulations. Create domestic manufacturing incentives that encourage competition rather than prohibition. Streamline Remote ID compliance to reduce cost and weight burdens. But most importantly, separate genuine security concerns from protectionist lobbying.

The drone hobby in America is under serious pressure. With it, so is the aviation talent pipeline that feeds our commercial and defense sectors. The December deadline approaches. The market continues constricting. The choices made in the next two months will determine whether American drone enthusiasts in 2026 face improved access or worsening restrictions.

What do you think? Are you seeing the impact of these market and regulatory pressures in your local drone community? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.