Opinion: DJI and The American Drone Delusion: We’re Not Catching Up, We’re Falling Behind

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

On December 23, 2025, the FCC added DJI to its Covered List, effectively banning the import and sale of any new DJI drones in the United States. Future DJI products will never legally reach American consumers. The ban, justified by a National Security Determination that arrived just two days before the deadline, represents the culmination of years of legislative effort to force Americans onto domestically manufactured alternatives.

There’s just one problem: those alternatives don’t exist. And they never will.

This is an opinion piece reflecting the analysis and perspective of DroneXL’s Editor in Chief.

After reporting on the drone industry for nearly a decade, watching the legislative theater around DJI unfold, and listening to politicians promise American drone dominance, I’m finally saying what everyone in this industry privately acknowledges but few dare to say publicly: the United States will never catch up to DJI. And the longer we pretend otherwise, the more damage we do to American operators, businesses, and public safety.

The numbers tell a story that no amount of lobbying money or political rhetoric can change. Here’s what you need to know:

- The Reality: DJI commands 70-90% of the global consumer drone market and 83.48% of all drone detections in operational theaters worldwide according to Dedrone‘s 2025 data.

- The Innovation Gap: China accounts for 79% of all global drone patents granted in 2024 and controls 87% of all drone patent filings since 2015. DJI alone has 18,937 patents globally.

- The Manufacturing Chasm: The entire US drone industry, roughly 500 companies combined, produces under 100,000 units annually. Meanwhile, Ukraine alone produces 2 million FPV drones per year through decentralized workshops.

- The Source: This opinion piece draws from eight years of drone industry reporting, government documents, and on-the-record statements from industry executives.

Why does the United States believe it can catch up to DJI?

Before we examine whether catching up is possible, we need to understand what we’re catching up to. DJI didn’t capture 70-90% of the global drone market through government subsidies or unfair trade practices. They did it by building products that customers actually want to buy.

DJI drones succeed because they deliver on five pillars simultaneously:

- Capability: DJI drones offer features that competitors struggle to match: Hasselblad cameras, omnidirectional obstacle avoidance, 4K/8K video, intelligent flight modes, and seamless software integration.

- Affordability: A DJI Mini 5 Pro costs under $800 and outperforms drones that cost three times as much from competitors. DJI’s vertical integration and supply chain efficiency translate directly to consumer value.

- Availability: Walk into any Best Buy, order from Amazon, visit a local camera shop. DJI drones are (were) everywhere, with robust inventory and distribution networks that competitors cannot match.

- Reliability: First responders trust DJI drones because they work, flight after flight, mission after mission. That reliability is earned through millions of hours of real-world operation and continuous refinement.

- Ease of Use: A first-time pilot can unbox a DJI drone and be flying safely within 15 minutes. The software is intuitive, the controls are responsive, and the learning curve is gentle. This accessibility opened the market to millions of users who would never have flown otherwise.

But there’s a sixth factor that makes DJI’s position even more entrenched: ecosystem lock-in.

DJI hasn’t just built drones. They’ve built an entire ecosystem that creates massive switching costs. Their Mobile SDK allows third-party developers to build specialized applications on top of DJI hardware. Hundreds of software companies, from mapping platforms like DroneDeploy and Pix4D to inspection solutions like DroneBase, have built their businesses around DJI integration.

Then there’s the payload ecosystem. DJI enterprise drones support thermal cameras from FLIR, multispectral sensors for agriculture, LiDAR systems for surveying, and spotlight and speaker modules for public safety. Customers have invested not just in DJI drones but in payloads, software licenses, training programs, and operational workflows built around DJI’s platform. That switching cost often exceeds the price of the drones themselves.

Matching DJI doesn’t mean building a drone that’s as good in one category. It means building a drone that’s as good in all five categories, simultaneously, at scale, while also replicating an ecosystem that took a decade to develop. No American manufacturer has come close.

The fundamental assumption behind every DJI ban, every Blue UAS mandate, and every “American drone independence” talking point is that US manufacturers just need time and a protected market to close the gap. This assumption is preposterous. We’ve had since at least 2017, when the US Army banned DJI drones, to close this gap. The Department of Interior grounded its fleet. Congress has passed restriction after restriction. And what has happened in those eight years? The gap has widened, not closed.

Consider the honest assessment from Blake Resnick, CEO of BRINC Drones, one of America’s most promising drone manufacturers. Speaking on the PiXL Drone Show in 2024, Resnick was remarkably candid:

“Even with unlimited resources, unlimited capital, unlimited access to talent, unlimited manufacturing capacity, BRINC would need at least three more years to catch up to DJI’s current technological capabilities.”

That’s the CEO of a Blue UAS manufacturer, backed by investors including OpenAI’s Sam Altman and Peter Thiel, admitting that even under fantasy conditions, his company couldn’t match where DJI is right now for another three years. But here’s the part nobody seems to acknowledge: DJI isn’t standing still. By the time American manufacturers reach where DJI is in 2026, DJI will be in 2030. The gap doesn’t close, it compounds.

How wide is the innovation gap between DJI and US manufacturers?

The innovation gap between DJI and American manufacturers isn’t measured in months; it’s measured in years, and that gap is accelerating. According to Mathys & Squire’s patent analysis, China was granted 6,217 drone patents in the past year alone, accounting for 79% of all global drone patents. The US? A distant second with a fraction of that output.

This isn’t just about patents on paper. This is about the foundational technology that makes drones work:

- Battery Technology: DJI drones achieve 40-46 minute flight times. Most American alternatives offer 20-30 minutes. That’s the difference between completing a mission and returning mid-operation for a battery swap.

- Obstacle Avoidance: DJI’s omnidirectional obstacle sensing has become table stakes for professional operations. Many Blue UAS alternatives have limited or no obstacle avoidance.

- Camera Systems: DJI’s integration of Hasselblad cameras, mechanical shutters, advanced image processing, and AI subject recognition represents years of development that competitors simply haven’t matched.

- Price-to-Performance: A leaked Department of Interior memo revealed that Blue UAS drones cost “8 to 14 times more” than comparable DJI platforms while reducing the department’s sensor capacity by 95% and meeting only 20% of mission requirements.

DJI employed over 14,000 people in 2024, with 25% of its workforce dedicated solely to product development. That’s roughly 3,500 engineers focused on nothing but making better drones. Compare that to Skydio, America’s largest drone manufacturer, which produces approximately 2,000 drones per month from its California facility. The scale difference is insurmountable.

What happened to all the companies that tried to compete with DJI?

The graveyard of DJI competitors should give pause to anyone who believes American manufacturers can simply “catch up” given enough time and protection.

- GoPro tried and failed. The company that revolutionized action cameras couldn’t translate that success to drones and abandoned the market entirely after the Karma’s disastrous launch.

- Sony tried and failed. Despite engineering prowess, manufacturing capability, and deep pockets, Sony’s Airpeak S1 launched at $9,000 for just the drone, with total system costs exceeding $15,000, possessed shockingly short battery life, and never gained meaningful market traction. Sony recently discontinued the product.

- Intel tried and failed. The chip giant poured resources into drone development and couldn’t compete.

- Parrot, the French manufacturer, was once DJI’s closest competitor. In 2020, CEO Henri Seydoux announced the company would no longer make consumer drones and would focus exclusively on professional and government markets, essentially conceding the consumer space to DJI.

- Skydio, widely considered America’s best hope for competing with DJI, has effectively conceded the consumer market. The company shifted away from the broader market because it couldn’t compete on price and capability, focusing instead on government and enterprise customers who are required by law to buy American.

If Sony and GoPro, companies with deep supply chains and world-class engineering, could not compete with DJI, why do we assume that startups with a fraction of their capital can do it?

Who actually benefits from DJI restrictions?

Follow the money. The companies lobbying hardest for DJI restrictions are the same companies that can’t compete with DJI on price, features, or capability. Skydio’s lobbying expenditures increased from $10,000 in 2019 to $560,000 in 2023 as the company pursued state-level bans after federal efforts stalled.

A June 2022 joint letter from six Blue UAS manufacturers openly advocated for legislation that would eliminate their primary competitor and create a captive customer base. They weren’t competing on merit; they were using investor money to purchase legislative outcomes.

Florida Senator Jason Pizzo captured this dynamic perfectly during a Senate Committee hearing when he accused a state official of “pimping for Skydio” after the official promoted the company during testimony about DJI restrictions.

The result? Florida’s DJI ban forced an estimated $200 million worth of perfectly functional public safety drones to be grounded. The state provided just $25 million for replacements, creating a $175 million funding gap. Orlando Police testified before the Florida Senate that DJI had zero failures in five years while approved Blue UAS replacements failed five times in 18 months, including a Skydio battery that caught fire through spontaneous thermal combustion while sitting on a deputy’s vehicle floorboard.

This isn’t security policy. It’s corporate welfare disguised as national defense.

Do counter-arguments hold up to scrutiny?

I’ve heard every argument for why American manufacturers can still win. None of them survive contact with reality.

The AI Leapfrog Theory: The most sophisticated counter-argument holds that the US doesn’t need to catch up on hardware because American companies lead in AI-driven autonomy. When drones become fully autonomous, the hardware gap becomes irrelevant.

Let me be clear: the United States does have a genuine lead in AI chip technology. NVIDIA, AMD, and the broader American semiconductor ecosystem are ahead of Chinese competitors in the most advanced AI processors. But the AI chips where America leads, the H100s and A100s that power large language models, are massive, power-hungry processors designed for server racks, not aircraft. The chips that actually go into drones are edge processors optimized for size, weight, and power consumption, a different market segment where China’s capabilities are far more competitive.

More fundamentally, AI chips are just one component. A drone also needs motors, batteries, cameras, gimbals, frames, sensors, antennas, and flight controllers. Having the best AI chip doesn’t help if you can’t affordably source the other 95% of the bill of materials.

And DJI isn’t just a hardware company. Their obstacle avoidance systems, Ocusync transmission, ActiveTrack subject following, and intelligent flight modes are all AI-driven. They employ 3,500 R&D engineers who aren’t sitting still while American startups try to leapfrog them.

Here’s the real test: Skydio’s entire value proposition IS autonomy. Their obstacle avoidance and autonomous flight capabilities are genuinely impressive, arguably best-in-class. And yet Skydio still couldn’t compete in the consumer market. They still lost the Army’s Short Range Reconnaissance contract to Red Cat. If autonomy were enough to leapfrog DJI, Skydio would already be winning. They’re not.

The Protected Incubator Theory: Another argument holds that government mandates create a “protected incubator” allowing American companies to survive until they reach scale and efficiency.

We’ve been running this experiment for eight years. The Blue UAS program launched in late 2020. The Pentagon spent $13-18 million developing alternatives to DJI. Federal agencies have been restricted from buying Chinese drones since the Trump administration. State after state has passed DJI bans for government use.

And what did this protected market produce? Drones that cost 8-14 times more, perform worse, and fail more frequently. Protected markets don’t drive innovation. They breed complacency. When companies know they have captive customers who legally cannot buy competitors’ products, they have zero incentive to improve quality or reduce prices. Blue UAS vendors raised prices because they could, not because their products justified the premium.

The Privacy Premium Theory: Some argue that enterprises will eventually pay an “American premium” for data sovereignty and trustworthy drones.

They already can. It’s called Blue UAS. The market for “trustworthy drones” exists right now, and it costs 8-14 times more while delivering 95% less capability. Meanwhile, DJI addressed data security concerns years ago with Local Data Mode, offline operation, and third-party app support. Multiple independent audits, including from Booz Allen Hamilton, FTI Consulting, and the Idaho National Laboratory, found no evidence of unauthorized data transmission. The vast majority of operators have concluded that DJI’s security mitigations are sufficient for their needs.

The Ukraine Model: Some point to Ukraine’s remarkable achievement, producing 2 million FPV drones annually through decentralized workshops, as proof that massive scale can be achieved outside China’s manufacturing model.

Context matters. Ukraine is producing disposable FPV drones for warfare, essentially flying grenades designed for single-use kamikaze attacks. A $400 FPV drone that flies once into a Russian tank is a fundamentally different product than a $2,000 Mavic 3 Pro with a 4/3-inch Hasselblad sensor, 43-minute flight time, and thousands of hours of reliable operation.

More importantly, Ukraine’s “decentralized” production still relies heavily on Chinese components. The motors, flight controllers, and electronic speed controllers flowing into Ukrainian workshops largely originate from the same Shenzhen supply chains that feed DJI. The lesson from Ukraine isn’t that America can replicate their model. It’s that even under existential pressure, with national survival at stake, a motivated country still depends on Chinese drone components.

Why can’t the United States just build its own drone components?

This is where the “catch up” fantasy completely falls apart. The problem isn’t just that DJI makes better drones. The problem is that China controls the entire supply chain from raw materials to finished components, and the United States has nothing comparable.

Start with raw materials. Rare earth elements are essential for the permanent magnets in brushless motors, the type of motor that powers virtually every consumer and commercial drone. China controls approximately 60% of global rare earth mining and, more critically, 90% of rare earth processing capacity. The neodymium magnets in drone motors, the lithium and cobalt in drone batteries, the supply chains all trace back to Chinese dominance at the extraction and refining level.

Lithium-ion batteries tell the same story. China manufactures 99% of lithium-ion battery cells used in drones. The FCC banned foreign drone batteries in December 2025, but you cannot ban your way out of supply chain dependence. When China sanctioned Skydio in October 2024, America’s flagship drone company was rationing parts within weeks. As Skydio CEO Adam Bry admitted: “The Chinese government will use supply chains as a weapon.” The New York Times reports analysts estimate it would take at least half a decade for US manufacturers to produce enough battery cells to meet domestic demand.

This raw material dominance translates directly to component costs. Colin Guinn, former CEO of DJI North America, explained the math in a Financial Times documentary: while American competitors paid nearly $10 per motor, DJI’s cost was as low as $2 thanks to vertical integration and proximity to suppliers. That’s a 5x cost disadvantage on a single component, and it compounds across every part of the drone.

But the most insurmountable advantage isn’t raw materials or component costs. It’s the ecosystem.

Shenzhen has evolved into the world’s hardware capital, a manufacturing ecosystem with no equivalent anywhere else on Earth. Within a few square miles, you can find suppliers for every component a drone requires: motors, ESCs, flight controllers, camera sensors, gimbals, injection-molded plastics, carbon fiber frames, battery cells, and specialized electronics. Engineers can prototype a new design, source components, and begin small-batch production within days. This ecosystem developed over decades of concentrated investment, infrastructure building, and specialization.

The United States has Silicon Valley for software. We have nothing comparable for hardware manufacturing. Building that ecosystem isn’t a five-year project. It’s a generational undertaking requiring massive capital investment, workforce development, and supply chain relocation that no one is seriously proposing, let alone funding.

The $1.4 billion “drone initiative” that politicians tout sounds impressive until you realize it’s a one-time investment that must compete with a company that plows hundreds of millions into R&D every single year, employs 3,500 engineers dedicated solely to product development, and is building on top of an existing industrial base that took decades to develop.

You cannot legislate an industrial ecosystem into existence. You cannot ban your way to manufacturing competitiveness.

DroneXL’s Take

I’ve been covering this industry since before the first DJI ban attempts. I’ve watched politicians promise American drone dominance for eight years. I’ve seen company after company try to compete with DJI and fail. I’ve documented the real-world consequences when agencies are forced to use inferior equipment.

The evidence is overwhelming: the US drone industry is not going to catch up to DJI. Not in four years. Not in seven years. Not ever, if we continue on this path.

The FCC’s December 23 decision didn’t just ban DJI. It locked American operators out of the global innovation curve permanently. While drone pilots in Europe, Asia, and the rest of the world gain access to each new generation of DJI technology, Americans will be frozen in time, unable to legally purchase whatever comes after the Mini 5 Pro, the Mavic 4 Pro, or the next revolutionary product DJI releases. The rest of the world moves forward. America stands still.

Catching up isn’t just about reaching where DJI is today. It’s about matching DJI’s pace of innovation, their scale of manufacturing, their depth of supply chain integration, and their patent portfolio. The gap isn’t static; it’s dynamic and widening. When BRINC’s CEO says he needs unlimited resources and three years just to reach current DJI capabilities, that’s an admission that American manufacturers are running a race they cannot win.

Anyone who tells you otherwise is either uninformed, financially motivated, or deliberately misleading you.

The strategic case for domestic drone manufacturing capability is sound. Reducing dependence on any single foreign supplier for critical technology makes sense. But the execution, banning proven technology without viable alternatives, enriching connected companies with captive government markets, forcing first responders to use equipment that costs 8-14 times more and performs worse, is catastrophically flawed.

My prediction: Five years from now, the United States will still be talking about American drone independence while DJI continues to dominate global markets. American operators who find ways to access DJI technology will maintain competitive capabilities. Those who can’t will fall further behind their global counterparts. And the gap will be wider than it is today, not smaller.

That’s not pessimism. That’s math.

Share your thoughts in the comments below. Am I wrong? Show me the data that suggests American manufacturers can close a decade-long technology gap while their target keeps moving forward.

Editorial Note: AI tools were used to assist with research and archive retrieval for this article. All reporting, analysis, and editorial perspectives are by Haye Kesteloo.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

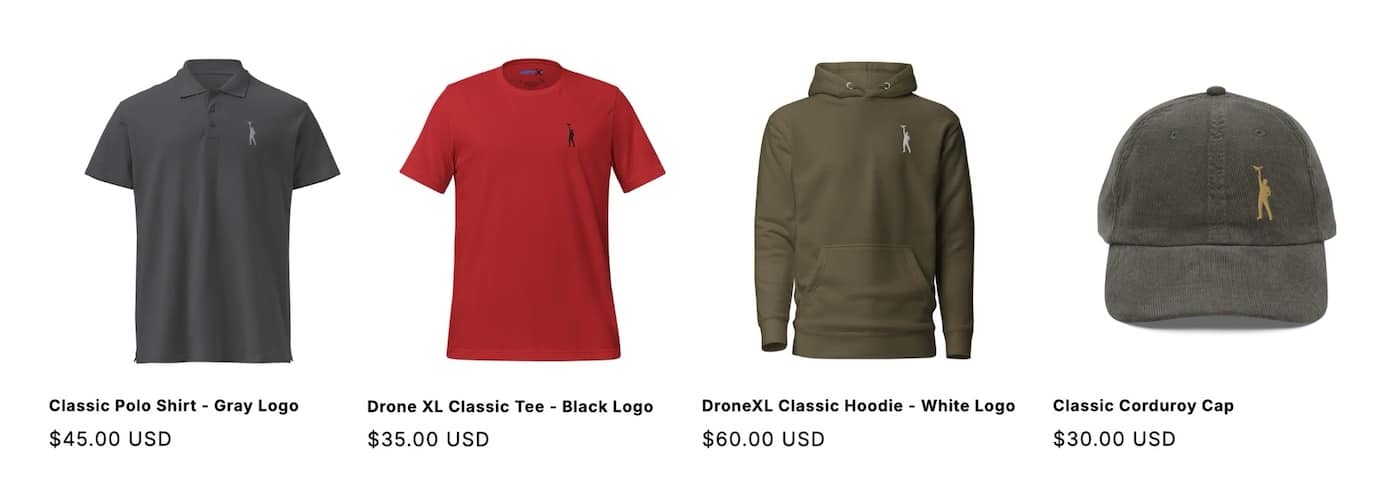

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.

A well-researched, well-reasoned analysis of a pathetic situation.

How is the FCC legally empowered to regulate things like electric motors, propellers and cameras that have nothing to do with the broadcast spectrum?

One more thing – I own four DJI drones. Three of them had time remaining on DJI Refresh policies I paid for before the ban, but now somehow are invalid in the United States. I now am operating without warranties or replacement insurance. How does national security or “American drone dominance” justify this taking by our government?

If DJI still can sell drones that were approved before the ban, why are those drones unable to have a warranty or crash insurance? DJI was happy to take my money and leave me with nada.

Thank you for commenting and you make some really good points!

Why did you wait until Friday to drop this piece? We call that a news dump in my world—this should have the chance to see the light of day during the work week.

In a perfect world…

Duh, another half brained idea from this creative lacking government. Where are they getting all this millions of dollars to find this new drone dominance? From my pockets and yours. And why the need to build so many military drones? Is there an upcoming war we don’t know about? Use half that money towards delegation and peace talks and we won’t need those drones. All I know is this government sucks and it needs to stay out of the people’s lives. You already messed around with napping now my drone? Your posting me off.

Simply put.. The USA politicians, lobbyists and sympathizers & promoters, have no Idea about Global economics, logistical analysis, product chain availability. Never mind simple math. Americans will not work for $25 a day with no benefits and work 6 days a week – 10 hours a day. As the big Taco-Man 🍊🤡 “Projectile-Vomits” nonsense… and others tremble for their pensions to keep face… It is just a plain FACT… the USA (and the rest of the G-7 countries.. can not compete with production costs or quality coming out of China. BRICS has a better shot than this whole Drone dominance proposal.

You are NOT wrong.

And to add to this, the US represented about 25% of DJI’s earnings, which is significant, but demand for drones in commercial use cases is increasing world-wide. China and India alone represent 34% of the world’s population, Asia collectively is 62,5%. Europe is another 9.24%, Africa 19.8%, while the US is just 4.1%.

The reality is that there are a LOT of new sales out there to be tapped outside the US, and with the current political climate in the US, a growing number of markets just don’t want to do business with the US anymore.

I think DJI will do just fine without the US, but I’m not at all sure the US will do well without DJI.