DJI Ban: Why Everyone Owes Drone Pilots Honest Answers

Check out the Best Deals on Amazon for DJI Drones today!

This week, DJI’s Head of Global Policy Adam Welsh sat down with YouTuber Faruk from iPhonedo for what was billed as a deep dive into the looming December 23 DJI ban. I watched the interview hoping for hard questions. What I got was a bit of a softball interview that left the most important issues untouched.

Welsh made his case against the DJI Ban. The “trap door” legislative design. The lack of a designated audit agency. The economic impact on American jobs. All valid points. But, unfortunately, Faruk never pressed hard on the questions that actually matter: China’s Article 7. The shell companies. The firmware hosted on DJI’s own servers under other brand names.

That interview sent me down a rabbit hole. And what I found is that the hard questions don’t stop with DJI. The US government has questions to answer about a legislative process that looks designed to fail. American drone companies have questions to answer about their lobbying and their own supply chain dependencies. And we, as an industry, have questions to answer about how we got here.

This article might upset some people. Good. It’s time we stopped playing softball and started asking the hard questions that matter.

The Hard Questions For DJI

1. The Shell Game: We Have the Receipts (And You Left Your Logo On Them)

Let’s be crystal clear: We are not speculating out of thin air. We are pointing to specific public records and technical analyses that anyone can review.

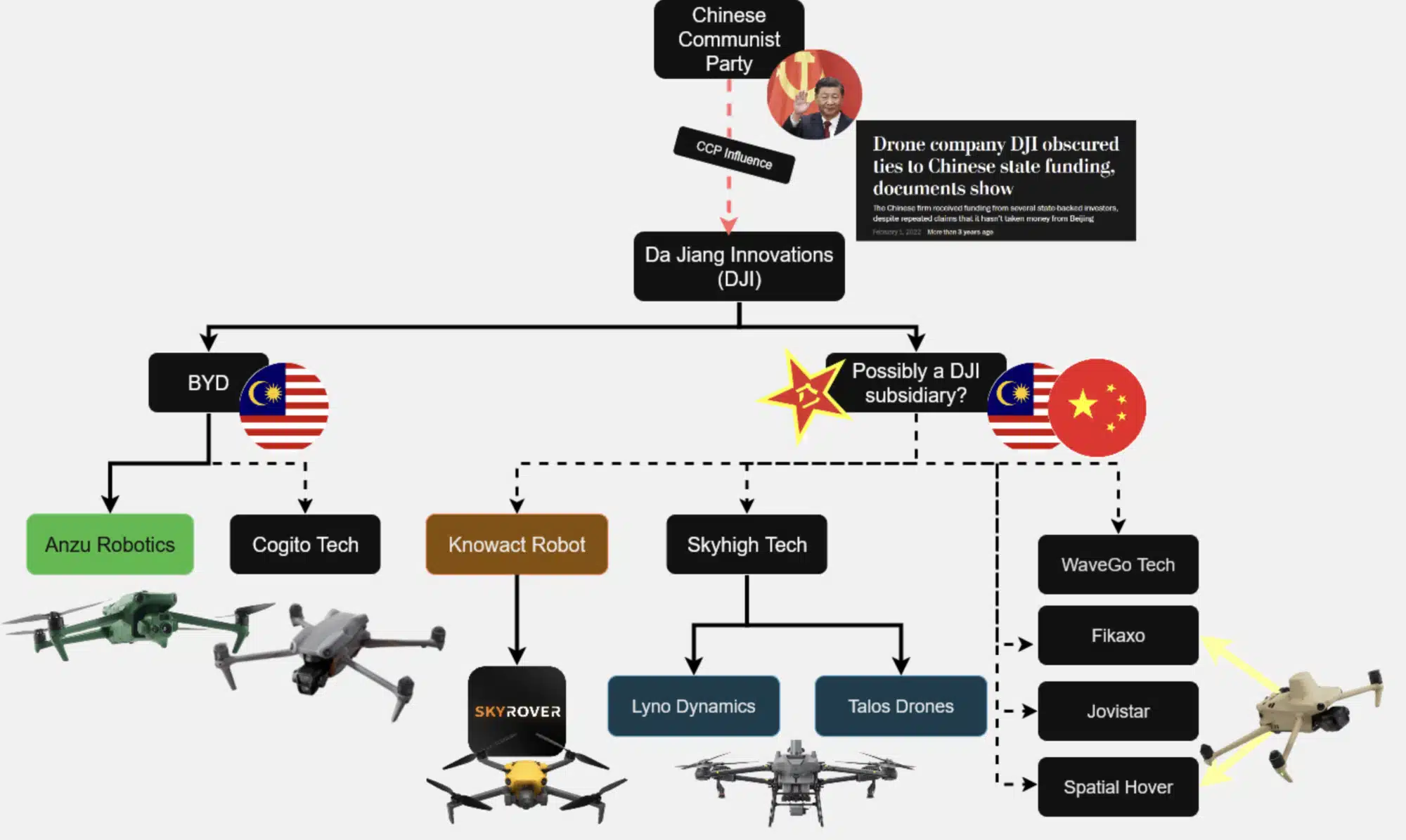

Thanks to the work of security researchers Kevin Finisterre (@d0tslash), Andreas (@Bin4ryDigit), Ian from Mad’s Tech, and Konrad Iturbe, combined with our own analysis of FCC filings, a troubling pattern appears to emerge: DJI-linked hardware and software repeatedly appears in the US market under other brand names through separate LLCs and shell entities. Many in the industry view this as a coordinated attempt to bypass growing regulatory and procurement barriers rather than a coincidence of similar designs.

The Lyno Dynamics Smoking Gun

On September 29, 2025, a company called Lyno Dynamics LLC filed paperwork with the FCC for a new drone controller (FCC ID: 2BQ98-LD220RC). The company is registered at a commercial registered‑agent address in Cheyenne, Wyoming, a model widely used in the state for mail‑forwarding and holding companies, including some anonymous shell and front companies, according to corporate transparency and anti-money-laundering (AML) experts.

The antenna specification sheet lists the brand as “SKYHIGH.” But in a mistake that is hard to ignore, the DJI logo is still visible at the top of the page. The engineers or contractors did not remove the DJI branding from the PDF before submitting it to the US Federal Government, strongly suggesting a direct connection between the “SKYHIGH” product and DJI’s internal documentation.

This isn’t an isolated incident. Researchers and our own reporting have documented a recurring pattern across multiple companies that appear to function as fronts or close partners for DJI hardware in US regulatory filings:

- Fikaxo Technology Inc (FCC ID: 2BQG9)

- Jovistar Inc (FCC ID: 2BGW)

- Spatial Hover Inc (FCC ID: 2BQ6A)

- Cogito Tech Company (FCC ID: 2BCHV)

- Anzu Robotics LLC (FCC ID: 2B8Y5)

Konrad Iturbe maintains a public GitHub repository aggregating these entities and their FCC filings. Anyone can verify the links, documents, and identifiers themselves.

The Digital Fingerprints

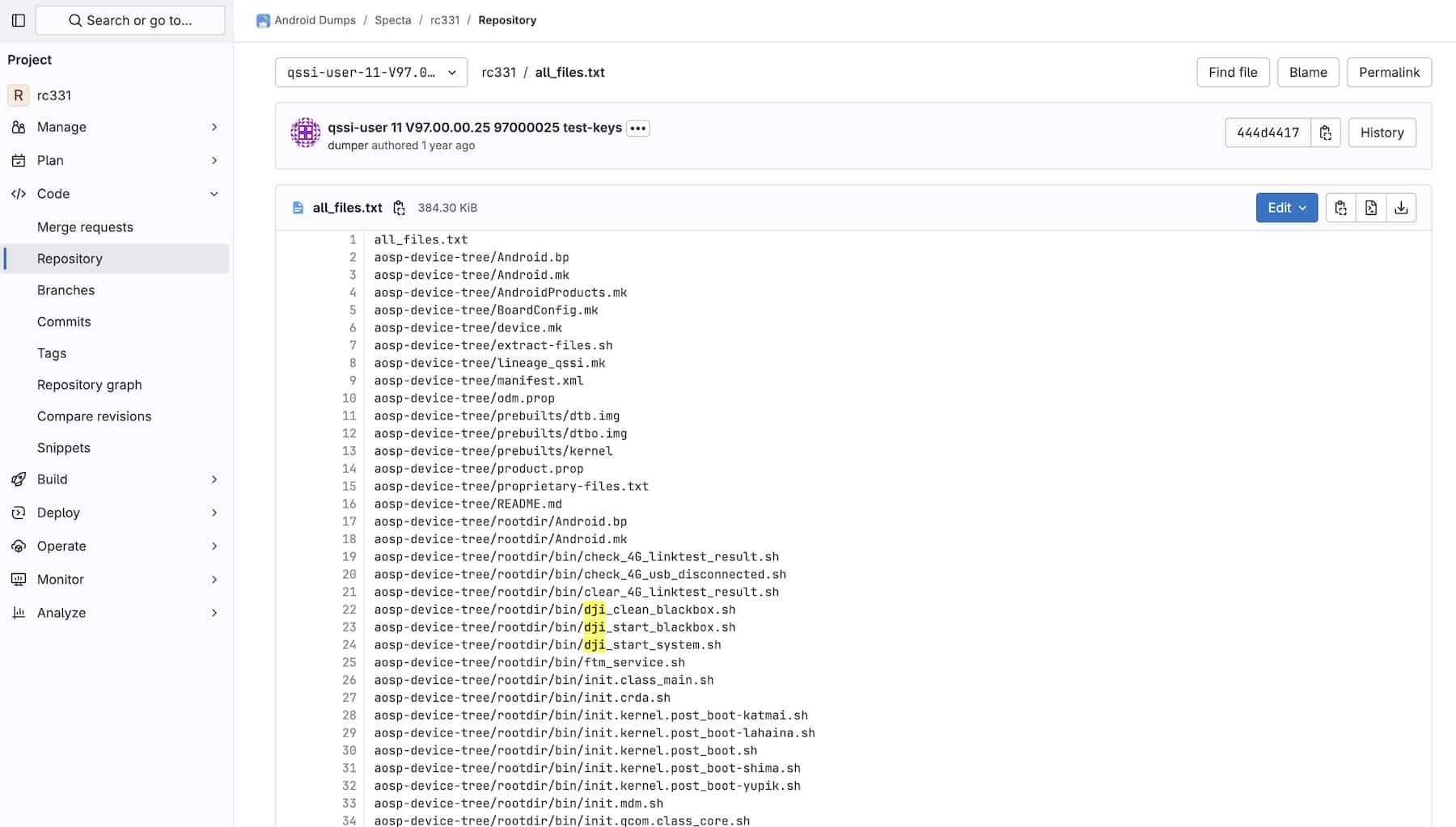

Companies like Specta and Cogito claim to be “independent innovators.” When researcher Kevin Finisterre emailed Specta asking about their relationship with DJI, they responded in writing: “SPECTA is a proud independent innovator in the industry and has no relationship with other drone companies.”

The technical evidence raises questions about the accuracy of that claim.

- Firmware for some of these “independent” drones is hosted on terra-2-g.djicdn.com, which is part of DJI’s own content delivery infrastructure. It is very difficult to square that with claims of complete independence when critical firmware images are being delivered from a competitor’s servers.

- Code dumps from the Specta firmware reportedly reveal 29 files with “DJI” in the filename, including dji_verify_self, dji_start_blackbox.sh, dji_decrypt, dji_config_store, and dji_mb_ctrl, suggesting shared code lineage rather than a clean-room, independent platform.

- Hardware analysis by Ian from Mad’s Tech concludes: “All PCB images even align. Does not appear to be separate production. Board PN all align. They are also using DJI’s ‘in-house’ P1 chipset for OcuSync that’s believed to be in-house ASIC. Has to be DJI supported as you can’t clone that.” That is one expert’s opinion, but it reinforces the impression of deep technical integration.

We first covered this pattern in March 2024 in our article “High-Flying Masquerade: DJI’s Shadowy Shell Game Unveiled.” Since then, additional filings and teardowns have strengthened the case that this is not a one-off anomaly but an ongoing strategy.

Questions for DJI:

- Lyno Dynamics LLC is registering hardware that appears to be DJI-designed under a new name. Is this done with your knowledge and authorization, or is this a distributor acting independently?

- If Specta is truly independent, why is its firmware hosted on djicdn.com? Why do its firmware images contain 29 files with “DJI” in the filename?

- DJI aggressively protects its intellectual property and has sued competitors for far less. If you believe these companies are not authorized to use your proprietary OcuSync technology and P1 chipsets, why haven’t you taken legal action? If you have authorized them, why not be transparent about those relationships?

- If FCC filings misrepresent the true manufacturer of a product, that’s not just a paperwork error—it could create exposure to serious legal consequences, potentially including allegations of wire fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1343) or conspiracy to defraud the United States (18 U.S.C. § 371). If regulators were to determine that any of these entities were created to willfully conceal the true manufacturer and bypass federal restrictions, the liability could extend beyond civil fines. Does DJI have any concerns about how these filings might be perceived by federal authorities?

Why this matters: This evidence, if left unaddressed, undermines any “innocent partner” narrative. It is hard to claim a purely transparent relationship with the US government while a web of branded entities files for approvals on DJI-linked hardware. It also gives US officials more reason to question DJI’s trustworthiness at exactly the moment that DJI claims it wants a fair audit.

2. Let’s Talk About Article 7 (The Law You Can’t Ignore)

This is the elephant in the room that DJI’s Head of Global Policy Adam Welsh didn’t address in his recent interview with YouTuber Faruk from iPhonedo, and that Faruk didn’t press on.

China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law includes Article 7, which states: “All organizations and citizens shall support, assist, and cooperate with national intelligence efforts.” Article 14 empowers intelligence agencies to demand that support. These provisions are not controversial; they are written into the law and are widely cited by legal analysts.

To DJI’s credit, the company has taken real steps to address data security concerns. In June 2024, DJI disabled flight records sync entirely for US users and removed thumbnail previews globally. Combined with Local Data Mode and the option to use third-party apps via DJI’s Mobile SDK, US operators now have significant control over what data, if any, leaves their devices.

In a November 2023 interview with Billy Kyle, Welsh stated: “We are not linked to the Chinese government. There’s no Chinese Golden Share, ICA, there’s no CCP member on our board, we don’t have any communist party members on, in senior roles or any other role. We are a privately held company.”

But here’s the problem: that’s not what Article 7 is about.

The 2017 National Intelligence Law doesn’t require government ownership, board seats, or party membership to apply. It covers all Chinese organizations and citizens by default. Welsh answered a question about government linkage. The harder question is about legal compulsion, and on that, DJI has been notably silent.

The US government’s core concern is not primarily about whether your flight logs are syncing to a server in Virginia or Shenzhen. The concern is that China’s National Intelligence Law could be interpreted to force DJI to assist state intelligence work in other ways: providing access to encryption keys, pushing compromised firmware updates, or building in capabilities that could be activated later.

No amount of “data doesn’t leave your device” addresses a scenario where the device itself becomes the vector.

It’s not just about them stealing your photos; it’s about a theoretical ‘kill switch’ that could ground 90% of US police drones instantly during a crisis, or a firmware update that subtly degrades GPS accuracy over specific regions.

Questions for DJI:

- Has the Chinese government ever requested access to source code, encryption keys, or the ability to push targeted firmware under the 2017 National Intelligence Law or any related statute?

- If the Ministry of State Security made such a demand tomorrow under Article 7, would DJI be legally able to refuse? Many outside legal observers suspect the answer is “no,” but your customers deserve to hear your official position.

- You disabled US flight sync in June 2024, a meaningful step. But does that protect against a firmware update pushed by engineers who are legally obligated to cooperate with Chinese intelligence if ordered to do so?

- What is DJI’s official legal position on Articles 7 and 14? Have you sought independent legal opinions on how these provisions apply to DJI, and if so, will you share the conclusions with your users and regulators?

Why this matters: Disabling sync was a good faith gesture, and we acknowledge it. But “we turned off the data pipeline” is not the same as “we can say no to Beijing.” The more fundamental question remains: If the Chinese government demands cooperation, can DJI legally refuse? If the honest answer is that you cannot, then US government concerns are not addressed by technical mitigations alone.

3. You Probably Can’t Win the UFLPA Argument

US Customs and Border Protection has been holding DJI shipments since October 2024 under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA). DJI has stated that its manufacturing happens in places like Shenzhen and Malaysia, not Xinjiang, and that it is committed to a clean supply chain.

Questions for DJI:

- Can you trace every gram of lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals in your batteries and motors to non-Xinjiang sources with documentation that will satisfy CBP’s standards?

- Realistically: Can any electronics manufacturer with significant Chinese supply chain exposure actually prove this to CBP’s satisfaction, given how far upstream mineral sourcing goes?

- What third-party audits or traceability programs has DJI commissioned or implemented specifically for UFLPA compliance, and will you publish those findings?

Why this matters: The UFLPA places the burden of proof on the importer, in effect creating a “rebuttable presumption” that goods with links to Xinjiang involve forced labor unless proven otherwise. If you can’t prove a negative with credible documentation, Customs can hold your drones indefinitely. That is less a misunderstanding to be cleared up and more a structural legal choke point that is hard for any China-exposed manufacturer to escape.

The Hard Questions For The US Government

DJI has uncomfortable questions to answer. So does Washington.

4. The “Trap Door” Was Built On Purpose

Adam Welsh was right about one thing: Section 1709, as structured, is set up so that inaction leads to a ban.

Congress mandated an audit but did not clearly assign a specific agency to conduct it. They set a 12-month deadline even though comprehensive security reviews often take longer. They made the penalty for missing the deadline an automatic ban. As Welsh revealed in his interview, “at the last minute the language was substituted” from an earlier compromise that actually designated an agency.

To many observers, this does not look like ordinary bureaucratic sloppiness. In practice, it functions like a legislative “pocket veto”: running out the clock in a way that achieves a ban without having to present a public evidentiary case.

Questions for Congress:

- Who inserted the final “trap door” language at the last minute, and what was the rationale?

- If DJI is considered a genuine national security threat, why rely on a procedural deadline to ban them? Why not declassify as much evidence as possible and ban them directly on the merits?

- Previous audits by Idaho National Labs, the Department of Interior, and the Pentagon’s consumer products office reportedly found no clear “smoking gun.” If those assessments are now considered insufficient or outdated, what new evidence has emerged?

- Is banning by bureaucratic default consistent with the spirit of due process, especially when tens of thousands of US users, businesses and agencies are affected?

Why this matters: It looks weak. Banning the world’s biggest drone maker primarily because “nobody had time to complete the audit” feeds the narrative that this is more about industrial policy and decoupling than about specific, demonstrable technical exploits. If there is compelling evidence, policymakers should show as much as they can. If not, they should be honest that this is a strategic decision about dependence on Chinese technology.

5. Is “Collateral Damage” the Strategy?

Let’s talk about first responders. Estimates suggest that over 90% of police and fire drone fleets in the US are currently made up of DJI or Autel platforms. A retroactive ban that revokes key approvals risks grounding them.

Arizona Fire Chief Luis Martinez warned: “In my opinion, lives are going to be lost because this air capability is going to be taken away.” That quote captures a broader concern shared by many emergency services leaders.

As we reported, police departments are already making opposite bets on equipment choices with taxpayer money, unsure whether their fleets will remain viable after December 23.

And “viable” doesn’t mean the drones stop flying. It means operational sustainability becomes uncertain: firmware updates that fix bugs or improve safety features may stop, replacement parts become harder to source, warranties may be voided or unenforceable, and insurance carriers may balk at covering equipment from a company on the Covered List.

For first responders who depend on reliable equipment for life-safety missions, these aren’t minor inconveniences.

Questions for the FCC and Administration:

- Have you modeled the likely impact on emergency response performance if large portions of current first responder drone fleets become non-compliant or lose critical capabilities?

- Why move to effectively ban the market leader before domestic alternatives can reliably produce enough equivalent units to fill the gap at comparable cost and capability?

- The FCC granted itself retroactive revocation authority in October. Do you intend to use it in this case? First responders need clarity on whether their existing fleets are at risk of being grounded.

Why this matters: If the government’s position is that decoupling from Chinese technology is worth a period of degraded emergency response capabilities, that is a debate the public deserves to have in the open. It is better to state that tradeoff clearly than to hide behind regulatory mechanisms and pretend there are no serious operational consequences.

6. Skydio’s Lobbying And Supply Chain Questions

We also have to talk about the American companies lobbying for this ban.

Skydio’s reported lobbying expenditures rose from roughly $10,000 in 2019 to about $560,000 in 2023, according to OpenSecrets.org. The company went from six registered lobbyists in 2019 to 24 lobbyists in 2023, per the same data. For a niche industry, this represents a massive, focused push—specifically targeting the committees that control this legislation. Skydio hired Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, paying $200,000 for Florida-focused lobbying efforts beginning in March 2021.

Their CEO Adam Bry testified before the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party in June 2024, in a hearing titled “From High Tech to Heavy Steel: Combatting the PRC’s Strategy to Dominate Semiconductors, Shipbuilding, and Drones”. During his testimony, Bry framed Chinese drones as a national security threat and told lawmakers that “the Chinese government has tried to control the drone industry, pouring resources into national champions and taking aim at competitors in the U.S. and the West.”

Yet Bry now insists Skydio “had nothing to do” with the Countering CCP Drones Act and claims the company has “not lobbied” for specific bans. In a July 2024 LinkedIn post responding to criticism, Bry wrote: “We had nothing to do with [the Countering CCP Drone Act] and have not lobbied in favor of it.“

Here’s what he does admit: Skydio holds “conversations with policymakers about the risks of Chinese drones” as part of its push for a “strong US drone industry.“

Call it what you want. When a company spends $560,000 on lobbying, testifies before Congress about the dangers of its main competitor, and openly discusses “risks of Chinese drones” with policymakers, the distinction between “advocating for a strong US industry” and “lobbying for a ban on Chinese competitors” becomes semantic.

Florida Senator Jason Pizzo captured the dynamic during a March 2023 Florida Senate hearing when he accused Florida DMS Secretary Pedro Allende of “pimping for Skydio” after Allende held up promotional material from the drone manufacturer during his testimony. “Don’t ever do that again. You’re pimping for a vendor right now. Shame on you!” Pizzo said.

A Collier County official, Sean Callahan, was terminated in January 2022 after it was discovered he secretly worked as a lobbyist for Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck—Skydio’s lobbying firm—while employed as the county’s deputy manager. A subsequent Florida Inspector General report found he was in “apparent” violation of the county’s conflict of interest policy.

When China sanctioned Skydio in October 2024, the company reportedly faced a serious supply challenge because its batteries were sourced from China. Skydio CEO Adam Bry warned that “the Chinese government will use supply chains as a weapon” at the same time his company had spent years urging the US government to use regulatory tools against DJI.

That contrast between public positioning and practical dependencies has not gone unnoticed.

Questions for Policymakers:

- How much of the push for a DJI ban is driven by classified national security assessments versus sustained lobbying by domestic competitors?

- If one goal is to reduce dependence on Chinese supply chains, what due diligence was done on the supply chains of Blue UAS and other approved domestic platforms before promoting them as “trusted” alternatives?

- Now that China has placed 11 US drone companies on its Unreliable Entity List, including Skydio and BRINC, how confident are policymakers that the American drone fleet is actually more secure or resilient under this tit-for-tat dynamic?

- As we’ve documented, US drone makers remain heavily dependent on Chinese components. Is current policy truly increasing security, or is it simply redistributing risk and creating chaos in the short term?

Why this matters: National security policy should be driven primarily by evidence and expert threat assessments. When companies that struggle to compete on product quality spend heavily to shape legislation against their rivals, critics argue that this looks less like pure security policy and more like protectionism wrapped in patriotic language.

The Hard Questions For All Of Us

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable. We need to ask ourselves some hard questions too.

7. Did We Have Any Other Choice Other Than DJI?

DJI controls an estimated 70% of the global drone market. Surveys of Drone Service Providers Alliance members indicate that roughly two-thirds say they would go out of business without DJI products. US estimates suggest over 90% of first responder drone fleets are currently made up of DJI or Autel aircraft. Welsh cited figures of 460,000 American jobs and $116 billion in economic activity tied in some way to DJI in the US market.

Critics might say we built an entire drone industry on products from a Chinese company subject to Chinese intelligence law. But let’s be honest about the alternatives that existed:

European options: Parrot’s Anafi line, launched in 2018, never matched DJI’s capability, reliability, or ecosystem. It remains a niche player.

American options: GoPro’s Karma drone failed in 2016 and the company exited the market entirely. Skydio launched in 2018 but has never been able to match DJI on price, availability, or breadth of capability. Skydio left the consumer drone market in 2023. Currently, their drones are significantly more expensive and focused almost exclusively on enterprise, first responder, and defense markets.

Other Chinese options: Autel and Yuneec offered alternatives, but they’re also Chinese companies subject to the same legal environment as DJI.

Even DJI itself couldn’t make American manufacturing work. In that same 2023 interview, Welsh revealed:

“We’ve made several investigations into [us manufacturing]. We were ready to start manufacturing facilities in California… but really the benefits don’t seem to accrue to us. Even if we manufactured, most of the attempts to ban Chinese drones focus on Chinese parts and Chinese software. So you’d really have to source all US parts, do the software from scratch. And what we found when we looked at that is that just jacks up the price to really untenable levels.”

If the world’s dominant drone manufacturer couldn’t make US production economically viable, what chance did startups have?

The uncomfortable truth is that there was (and is) no viable non-Chinese drone industry to build on. American and European manufacturers either failed to compete, couldn’t achieve scale, or never offered products that met the needs of recreational fliers, commercial operators, and first responders at accessible price points.

Questions we should be asking instead:

- Why did American and European drone companies fail to compete with DJI for over a decade?

- What policy failures allowed a single Chinese company to capture 70% of a strategically important global market with no credible Western alternative emerging?

- If national security concerns about Chinese technology have existed since at least 2017, why didn’t the US government invest in building domestic alternatives BEFORE moving to ban the market leader?

- Is it fair to blame operators for “choosing” DJI when DJI was effectively the only choice that worked?

The drone industry didn’t choose dependency on China. The drone industry IS dependent on China, because no one else showed up.

8. Is Decoupling Worth The Pain?

The US government’s emerging position on Chinese technology is that decoupling will be painful and that some pain is acceptable to reduce long-term strategic dependence. But the pain isn’t always one-sided.

When China sanctioned Skydio in October 2024, cutting off access to Chinese-made batteries, it demonstrated exactly what the US fears about supply chain dependence, except this time the weapon was aimed at an American company. The same vulnerability the US government cites as a reason to ban DJI exists in reverse for domestic manufacturers who still rely on Chinese components.

The question is whether the scale and timing of that pain are proportionate to the risks being addressed, and who bears the costs.

Questions for everyone:

- Is building a more domestic or allied drone industry worth a period of higher prices and reduced capabilities for first responders, farmers, and commercial operators?

- How many years of less capable, more expensive drones are acceptable in the name of supply chain independence?

- If American lives are lost or missions fail because first responder drone capabilities are degraded during the transition, is that an acceptable cost, and who should be accountable for that decision?

- Or is the “national security” framing sometimes being used as cover for protectionist policies that will ultimately raise costs for American consumers and operators while concentrating benefits among a small group of politically connected manufacturers and investors?

We don’t have clean answers. Anyone who claims they do is probably trying to sell you hardware, a policy, or a narrative.

The battlefield reality: While we debate consumer drone bans, Ukraine has demonstrated that cheap, mass-produced drones are now decisive weapons of war. Ukrainian operators are modifying $1,000 DJI drones to drop grenades, while US defense contractors struggle to produce alternatives at scale. The irony is stark: the same Chinese technology we’re banning for “national security” reasons is being used by a US ally to defend against Russian aggression. If the goal is military readiness, banning access to the world’s most capable drone technology may achieve the opposite.

DroneXL’s Take: The Ugly Truth

DroneXL is a US-based publication. We are pro-America. We want a thriving domestic drone industry.

We are also pro-free-market and pro-reality. We believe competition makes everyone better and that trying to legislate your way to industrial success is a risky and often losing strategy.

These values are in tension right now, and we’re not going to pretend otherwise.

Here is the ugly truth that few want to say out loud:

DJI’s credibility with US policymakers is badly damaged. The combination of China’s intelligence laws and the pattern of DJI-linked hardware appearing under other brands in FCC filings has led many in Washington to view DJI as a strategic risk rather than just a successful consumer electronics company. DJI may dispute that framing, but the perception is real, and the burden is now on them to address it with transparency and verifiable answers.

The US government is choosing speed over transparency with the public. The structure of Section 1709 and the December 23 deadline makes it look less like an earnest attempt to conduct a timely audit and more like a mechanism to accelerate decoupling without a detailed public evidentiary record. US officials may have classified information they believe justifies this, but they have not shared enough with the people and agencies who will live with the consequences.

The lobbying game around drones is unusually aggressive. American drone companies that have struggled to match DJI’s price-performance profile have invested heavily in lobbying for restrictions on Chinese competitors. At the same time, some of those companies still rely on Chinese components and are now themselves targets of Chinese sanctions. The private equity playbook of regulatory capture followed by consolidation and higher prices is starting to appear in the drone space, and operators should be aware of that dynamic.

A rushed or poorly planned ban will hurt real people. First responders risk losing capabilities they currently depend on. Search and rescue operations could be degraded. Farmers may face higher costs. Some small drone service businesses say they may not survive a rapid transition away from Chinese platforms. These are not abstract policy debates; they are real operational consequences that will affect real Americans, while lobbyists and legislators personally absorb far less of the risk.

But our dependency on Chinese technology is also a real vulnerability. We cannot pretend that building critical workflows and infrastructure on products from a country with adversarial interests and compulsory intelligence-cooperation laws carries no risk. As an industry, we made choices that got us here, often with eyes wide open.

The innovation problem nobody mentions: Banning DJI in America doesn’t stop DJI from innovating. It stops Americans from accessing those innovations. While US operators are forced onto less capable platforms, DJI will continue releasing next-generation technology for the rest of the world. European farmers will have better agricultural drones. Asian infrastructure inspectors will have better tools. American competitors, protected from competition, will have less pressure to innovate. In five years, we may find ourselves not just behind on manufacturing – but behind on capability, training, and operational experience. Protectionism doesn’t pause the global technology race. It just takes America out of it.

The December 23 deadline is five days away. The trap door is open. Waiting for a hero to untangle this mess is not a strategy.

What we want is honesty. From DJI about the legal constraints it operates under and its relationships with the shell companies and partners showing up in FCC filings. From the US government about the real motivations and evidence behind these policies. From American drone companies about their lobbying activities and supply chain dependencies. From ourselves about the choices and tradeoffs that created this dependency in the first place.

We’re going to keep asking the hard questions. If you have information, reach out. If you have documents, we protect sources.

Because the biggest question of all is the one nobody seems willing or capable to answer:

What is the best way forward?

Not for DJI. Not for Skydio. Not for the politicians or the lobbyists. But, What is the best way forward for the drone pilots, the first responders, the search and rescue teams, the farmers, and the small business owners who just want capable, reliable and affordable tools to do their jobs.

Is it a hard decoupling that accepts short-term pain for long-term independence? Is it a managed transition with realistic timelines and actual domestic alternatives? Is it an honest audit that either clears DJI or presents real evidence? Or is it something else entirely?

We don’t have the answer. But we know it won’t come from softball interviews, legislative trap doors, or lobbyists writing checks. It will come from asking the hard questions and demanding honest answers from everyone involved.

That’s what we intend to keep doing.

What do you think? Is the DJI ban justified national security policy or protectionism in disguise? Is DJI an unfairly targeted company, or does it still owe the industry honest answers about Article 7 and the shell company pattern? Are American drone operators innocent collateral damage or co-architects of their own vulnerability?

Tell us in the comments.

Discover more from DroneXL.co

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Check out our Classic Line of T-Shirts, Polos, Hoodies and more in our new store today!

MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD

Proposed legislation threatens your ability to use drones for fun, work, and safety. The Drone Advocacy Alliance is fighting to ensure your voice is heard in these critical policy discussions.Join us and tell your elected officials to protect your right to fly.

Get your Part 107 Certificate

Pass the Part 107 test and take to the skies with the Pilot Institute. We have helped thousands of people become airplane and commercial drone pilots. Our courses are designed by industry experts to help you pass FAA tests and achieve your dreams.

Copyright © DroneXL.co 2026. All rights reserved. The content, images, and intellectual property on this website are protected by copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of any material without prior written permission from DroneXL.co is strictly prohibited. For permissions and inquiries, please contact us first. DroneXL.co is a proud partner of the Drone Advocacy Alliance. Be sure to check out DroneXL's sister site, EVXL.co, for all the latest news on electric vehicles.

FTC: DroneXL.co is an Amazon Associate and uses affiliate links that can generate income from qualifying purchases. We do not sell, share, rent out, or spam your email.

Excellent article. I have no hope that US law- and policymakers will read it. A total failure of our “system” with dire consequences on the horizon.

Thank you!

They pardon a cocaine trafficker who has trafficked TONS of cocaine into America but they ban “suspect” Chinese drones.

“2. Let’s Talk About Article 7 (The Law You Can’t Ignore)”

This is an impossible to win argument for DJI – literally. It’s a provable fact that you cannot prove a negative and your question, essentially is “Prove you are not complying and never will comply with the Chinese government in a request to see drone users’ data or spy on them.” As you note, they have taken steps that make it harder for themselves to spy on user data, but it’s always possible to do that.

They have also shown their source code to US gov agencies and have never been shown to have malicious code, but much like people who believe open source software ensure transparency, it’s only true if everyone plays nice.

I used to work as a developer for an eVoting machine company and I had hands on experience with exactly this problem: how do we prove we’re not cheating? It’s amazingly difficult.

“3. You Probably Can’t Win the UFLPA Argument

-Can you trace every gram of lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals in your batteries and motors to non-Xinjiang sources with documentation that will satisfy CBP’s standards?

-Realistically: Can any electronics manufacturer with significant Chinese supply chain exposure actually prove this to CBP’s satisfaction, given how far upstream mineral sourcing goes?”

I’m glad you added the second line in there because the first is something that I’m betting NO hardware maker in any country – regardless of where they get their parts – can do. It’s dangerous to think in a China vs the World perspective because it’s just not even close to that simple. It’s also kind of weirdly convenient that with all the other similar abuses around the world and the raw material producers involved, it’s only China the US gov is concerned about. I don’t see the CBP stopping deBeers diamonds from entering the US but they have a pretty spotty human rights record that’ make DJI look like saints.

The reality is that DJI has worked hard to stay clean. They’ve repeatedly allowed government and security agencies to review their code. There are no examples of their breaking security trust by intent or direct action. And yes, they are trying to find ways to get around these issues – they ARE a business and want to find ways to stay in business.

In the end though, for anyone outside the US, it seems pretty obvious that these actions are less about security as it is trying to find a quasilegal way to shut down a company that’s a strong leader in a market the US is not well represented in. They couldn’t find any egregious behaviours like they could with ZTE and Huawei. So they cooked up this trapdoor scheme that only requires the US gov to do nothing – prove nothing – for DJI to effectively be shut down in terms of future products.

On the other hand, the US is only 25% of DJI’s revenue and no one else seems to see the security issues the US does (which is itself a telling clue). This won’t kill DJI, but it will harm the US. I suspect, much as the rest of the world is slowly deciding to do, DJI’s best choice to say “goodbye” to the US market and go where they’re more appreciated.

Thank you for your comments. Yeah it is quite the situation…

Fun(?) fact: the primary author of this legislation, Elise Stefanik, just announced she is ending her governor campaign in NY and will not be running for reelection. She also has a former staffer on the Skydio board of directors and has received sizable donations from them.

Thank you for a very thorough breakdown of the DJI drone ban situation. As an owner /operator of a small Drone service business, I am completely dependent on DJI technology to operate. I understand the risks of national security and would love to see America competitive within this market. Unfortunately, as you stated, we are years away from that reality. The American Drone service industry is getting ready to enter a long dark winter. My hope is that operators such as myself can survive with older tech until viable and affordable alternatives show up on the US market.

Thank you for commenting. We hear you loud and clear! 👍

This is one of the best written articles I have ever seen. Thank you for writing it and I appreciate the ability to read it.

The ONLY way this is going to end is if Americans step up to there legislatures and the US Government and ignite some raging fires under there butts and get DJI unbanned. If Americans don’t do that then were royally screwed! This isn’t going to be possible if only a few thousand people step up the government, power happens in numbers now if a FEW MILLION people stepped up to Government and said they want DJI back that might make them turn there heads! Otherwise I hope DJI turns all there drones into bricks and tells people the sooner you get us unbanned, the sooner we will unbrick your drones! Because I see that as a power move for DJI!

I want to record my kids adventures and my boys golf trips on a high quality reliable device. If china wants so see me shoot 20 over or watch a teenager drop a ball, feel free. This seems overreach and risiculous

I’m not a drone operator but have sympathy for those who rely on DJI.

As I understand, the US doesn’t plan on banning existing DJI drones on December 23. So business can continue to operate. At this point, it is speculation what will happen to support, spare parts, etc.

As your article says, DJI is being deceitful about trying to setup shadow companies to get around US laws.

China is not trustworthy. They have enacted policies to unfairly eliminate competition in industries such as steel, rare earths, solar panels and have succeeded.

It is the official policy of China to become the dominant economic and military power at the expense of the US.

They have occupied the South China Sea at the detriment of other countries with valid claims to the area and ignored the result of a legal case which they lost.

They have stolen US technology and forced US (and other countries companies) to disclose trade secrets in order to operate in China.

What happens when China invades Taiwan and we get in a military conflict with China? Highly likely China will invoke Article 7 with any Chinese company doing business in the US to cause havoc in the continental US and our allies.

The DJI share of US drone market is between 1 to 2 billion dollars. With that size market, highly probable a US or non-Chinese company will step in.

This is a good, long-overdue article. I would like to reinforce another commenter’s note that no other friendly country is even considering such a ban on DJI, and these countries have their own impressive intelligence and counterintelligence organizations. Why are none of them concerned? Another point that may need some expansion relates to the Chinese law requiring intelligence cooperation if the government demands it. Does anyone believe a practical counterpart to this doesn’t exist here in the U.S.? In times of war, American companies have been, and likely would be expected to be nationalized in whole or in part. So what’s the practical difference?

I think all points are valid but the US lost this. WE are the only ones who have an issue with DJI. HOW is DJI supposed to prove themselves when no agency will step forward to evaluate? The US is a SPITEFUL country. We all need to admit it. Lobbyists trying to keep DJI out are quite the hypocrites. If our drones still rely on Chinese tech or parts, what’s the point!? Funny how we will go to china for cheaper parts but yell “Murica!” If Americans were truly about America, why are we importing cheap parts rather than actually concentrating on making better, financially competitive products? Short answer is BECAUSE WE CANT! But no, getting Chinese parts is good fiscal practice when it saves cost but not cool when it’s too good for us to compete. We try to enter the race late and then try to freeze out the best and HAVE NO COMPETITIVE PRODUCTS. Dumb!

Pretty much spot on. Thank you for commenting.

Why isn’t there prominent mention of BRINC and their role in this legislation? Especially after the recent Forbes article: https://www.forbes.com/sites/zoyahasan/2025/12/03/this-25-year-old-founder-wants-to-kick-chinese-drones-out-of-american-skies/

Because of limited resources. Thank you for passing this article along. We will definitely look into that.